The search for truth is not exclusive to representational art. From viewing many of the examples so far, you can see how individual artists use different styles to communicate their ideas. Style refers to a particular kind of appearance in works of art. It’s a characteristic of an individual artist or a collective relationship based on an idea, culture, or artistic movement. Following is a list and description of the most common styles in art:

Naturalistic

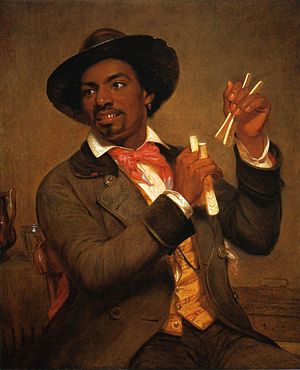

William Sydney Mount, The Bone Player, 1856, oil on canvas, 36 x 29 in

A naturalistic style uses recognizable images with a high level of accuracy in their depiction. Naturalism also includes the idealized object: one that is modified to achieve a kind of perfection within the bounds of aesthetics and form. William Sydney Mount’s The Bone Player gives accuracy in its representation and a sense of character to the figure, from his ragged-edged hat to the button missing from his vest. Mount treats the musician’s portrait with a sensitive hand, more idealized by his handsome features and soft smile.

Abstract

Marsden Hartley, Landscape, New Mexico, c. 1916. Pastel on paper. The Brooklyn Museum, New York

An abstract style is based on a recognizable object, which is then manipulated by distortion, scale issues, or other artistic devices. Abstraction can be created by exaggerating form, simplifying shapes, or using strong colours. Let’s look at three landscapes with varying degrees of abstraction in them to see how this style can be so effective. In the first one, Marsden Hartley uses abstraction to give the piece Landscape, New Mexico a sense of energy. Through the rounded forms and gesture in treatment, we can discern hills, clouds, a road, and some trees or bushes.

Georgia O’Keeffe’s Birch and Pine Trees – Pink, 1925 combines soft and hard abstraction into a tree-filled landscape dominated by a spray of orange paint suggesting a branch of birch leaves at the top left. Vasily Kandinsky’s Landscape with Red Spots, No. 2 goes further into abstraction, releasing colour from its descriptive function and vastly simplifying forms. The rendering of a town at the lower left is reduced to blocky areas of paint and a black triangular shape of hill in the background. In all three of these, the artists manipulate and distort the so-called real landscape as a vehicle for emotion.

Roman bust of Sappho, Capitoline Museum, Rome

The definition of abstract is relative to cultural perspective. That is, different cultures develop traditional forms and styles of art that are understand within the context of a particular culture (see the following section on cultural styles) and that may be difficult for another culture to understand. So, what may be stylistically abstract to one culture could be more realistic to another. For example, the Roman female bust looks very real from a western European aesthetic perspective.

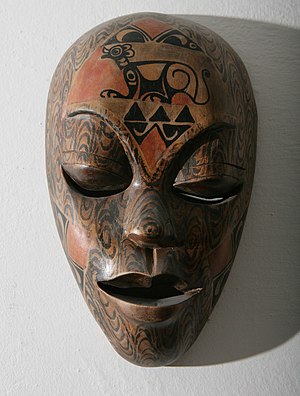

African wooden mask

From the same perspective, the African mask would be considered abstract. Yet, to the African culture from which the mask emerged, it would appear more realistic.

In addition, the African mask shares some formal attributes, such as the exaggerated eyes and mouth and the painted lines and designs, with those found on the Tlingit Groundhog Mask from Canada’s west coast. It’s very possible that the cultural perspective of these two cultures would consider the Roman bust as abstract. So, it’s important that we understand artworks from cultures other than our own in the context in which they were originally created.

Questions of abstraction may also emerge from something as simple as our distance from an artwork. View Fanny/Fingerpainting by American painter and photographer Chuck Close. At first glance, it is a highly realistic portrait of the artist’s grandmother-in-law. Click the image to view a large version. Note how the painting dissolves into a grid of individual fingerprints, a process that renders the surface very abstract. With this in mind, we can see how any work of art is essentially made of smaller abstract parts that, when seen together, make up a coherent whole.

Non-objective

Non-objective imagery has no relation to the so-called real world; that is, the work of art is based solely upon itself. In this way, the non-objective style is completely different than abstract, and it is important to make the distinction between the two. This style rose from the modern art movement in Europe, Russia, and the United States during the first half of the 20th century. Pergusa Three by American painter and printmaker Frank Stella uses organic and geometric shapes and strong colour set against a heavy black background to create a vivid image. More than with other styles, issues of content are associated with a non-objective work’s formal structure.

Cultural styles

Tlingit, Groundhog Mask, c. 19th century; carved and painted wood, animal hair; collection the Burke Museum, University of Washington, Seattle; used by permission

Cultural styles refer to distinctive characteristics in artworks throughout a particular society or culture. Some main elements of cultural styles are recurring motifs, created in the same way by many artists. Cultural styles are formed over hundreds or even thousands of years and help define cultural identity. Let’s find evidence of this style by comparing two masks; one from Alaska and the other from Canada. The Yup’ik dance mask from Alaska is stylized with oval and rounded forms divided by wide bands in strong relief. The painted areas outline or follow shapes. Carved and attached objects give an upward movement to the whole mask, and the face carries an animated expression.

By comparison, the Groundhog Mask (right) from the Tlingit culture in coastal northwestern Canada exhibits similar forms and many of the same motifs. The two mouths are particularly similar to each other. Groundhog’s visage takes on human-like characteristics just as the Yup’ik mask takes the form of a bird. This cultural style ranges from western Alaska to northern Canada.

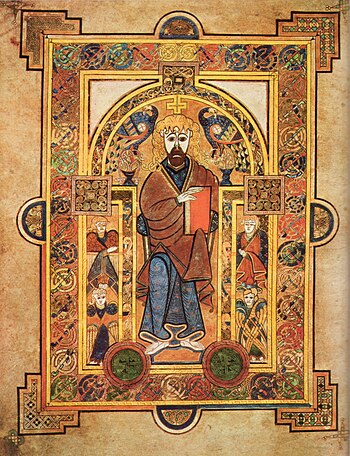

Page from the Book of Kells, around 800 CE. Trinity College, Dublin

Celtic art from Great Britain and Ireland shows a cultural style that’s been identified for thousands of years. Its highly refined organic motifs include spirals, plant forms, and zoomorphism. Intricate and decorative, the Celtic style adapted to include early book illustration. The Book of Kells is considered the pinnacle of this cultural style.

Descriptive Questions

Answer these questions in your journal:

- If you make art: What kind is it? What medium do you use? What style is it?

- If you don’t make art: Apply the previous questions to art that you typically appreciate.

The search for truth is not exclusive to representational art. From viewing many of the examples so far, you can see how individual artists use different styles to communicate their ideas. Style refers to a particular kind of appearance in works of art. It’s a characteristic of an individual artist or a collective relationship based on an idea, culture, or artistic movement. Following is a list and description of the most common styles in art:

Naturalistic

A naturalistic style uses recognizable images with a high level of accuracy in their depiction. Naturalism also includes the idealized object: one that is modified to achieve a kind of perfection within the bounds of aesthetics and form. William Sydney Mount’s The Bone Player gives accuracy in its representation and a sense of character to the figure, from his ragged-edged hat to the button missing from his vest. Mount treats the musician’s portrait with a sensitive hand, more idealized by his handsome features and soft smile.

Abstract

An abstract style is based on a recognizable object, which is then manipulated by distortion, scale issues, or other artistic devices. Abstraction can be created by exaggerating form, simplifying shapes, or using strong colours. Let’s look at three landscapes with varying degrees of abstraction in them to see how this style can be so effective. In the first one, Marsden Hartley uses abstraction to give the piece Landscape, New Mexico a sense of energy. Through the rounded forms and gesture in treatment, we can discern hills, clouds, a road, and some trees or bushes.

Georgia O’Keeffe’s Birch and Pine Trees – Pink, 1925 combines soft and hard abstraction into a tree-filled landscape dominated by a spray of orange paint suggesting a branch of birch leaves at the top left. Vasily Kandinsky’s Landscape with Red Spots, No. 2 goes further into abstraction, releasing colour from its descriptive function and vastly simplifying forms. The rendering of a town at the lower left is reduced to blocky areas of paint and a black triangular shape of hill in the background. In all three of these, the artists manipulate and distort the so-called real landscape as a vehicle for emotion.

The definition of abstract is relative to cultural perspective. That is, different cultures develop traditional forms and styles of art that are understand within the context of a particular culture (see the following section on cultural styles) and that may be difficult for another culture to understand. So, what may be stylistically abstract to one culture could be more realistic to another. For example, the Roman female bust looks very real from a western European aesthetic perspective.

From the same perspective, the African mask would be considered abstract. Yet, to the African culture from which the mask emerged, it would appear more realistic.

In addition, the African mask shares some formal attributes, such as the exaggerated eyes and mouth and the painted lines and designs, with those found on the Tlingit Groundhog Mask from Canada’s west coast. It’s very possible that the cultural perspective of these two cultures would consider the Roman bust as abstract. So, it’s important that we understand artworks from cultures other than our own in the context in which they were originally created.

Questions of abstraction may also emerge from something as simple as our distance from an artwork. View Fanny/Fingerpainting by American painter and photographer Chuck Close. At first glance, it is a highly realistic portrait of the artist’s grandmother-in-law. Click the image to view a large version. Note how the painting dissolves into a grid of individual fingerprints, a process that renders the surface very abstract. With this in mind, we can see how any work of art is essentially made of smaller abstract parts that, when seen together, make up a coherent whole.

Non-objective

Non-objective imagery has no relation to the so-called real world; that is, the work of art is based solely upon itself. In this way, the non-objective style is completely different than abstract, and it is important to make the distinction between the two. This style rose from the modern art movement in Europe, Russia, and the United States during the first half of the 20th century. Pergusa Three by American painter and printmaker Frank Stella uses organic and geometric shapes and strong colour set against a heavy black background to create a vivid image. More than with other styles, issues of content are associated with a non-objective work’s formal structure.

Cultural styles

Cultural styles refer to distinctive characteristics in artworks throughout a particular society or culture. Some main elements of cultural styles are recurring motifs, created in the same way by many artists. Cultural styles are formed over hundreds or even thousands of years and help define cultural identity. Let’s find evidence of this style by comparing two masks; one from Alaska and the other from Canada. The Yup’ik dance mask from Alaska is stylized with oval and rounded forms divided by wide bands in strong relief. The painted areas outline or follow shapes. Carved and attached objects give an upward movement to the whole mask, and the face carries an animated expression.

By comparison, the Groundhog Mask (right) from the Tlingit culture in coastal northwestern Canada exhibits similar forms and many of the same motifs. The two mouths are particularly similar to each other. Groundhog’s visage takes on human-like characteristics just as the Yup’ik mask takes the form of a bird. This cultural style ranges from western Alaska to northern Canada.

Celtic art from Great Britain and Ireland shows a cultural style that’s been identified for thousands of years. Its highly refined organic motifs include spirals, plant forms, and zoomorphism. Intricate and decorative, the Celtic style adapted to include early book illustration. The Book of Kells is considered the pinnacle of this cultural style.

Activity

Descriptive Questions

Answer these questions in your journal:

Content is available under the

Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike License.

Privacy Policy | Authors