Aboriginal people are intimately identified with their country (land) and everything that is on that land.

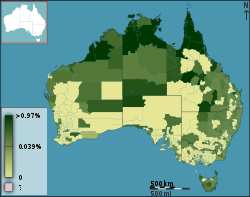

View this map of Australia.

- Whose country are you on?

- Have you ever seen this map before? If not, why do you think you have not come across it before?

What the map attempts to do:

Both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders as a percentage of the population, 2011

The map represents research carried out for the Encyclopaedia of Aboriginal Australia (Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, 1994). This publication contains more detailed information than is available on the map.

The research method was to use the published resources available between 1988 and 1994. The map was then created as a graphic illustration. It indicates only the general location of larger groupings of people, which may include smaller groups such as clans, dialects or individual languages in a group.

What the map doesn’t attempt to do:

- The Aboriginal Australia map does not claim to be definitive and is not the only source of information about language and social groups.

- The information in the map is contested and may not be agreed to by some landowners.

- The boundaries are not intended to be exact and as it was produced before native title legislation, the map is not suitable for use in native title or other land claims.

Dreaming stories are strongly connected with place. All life is interconnected with country; thus people are connected to the land, other people and all living things through the land.

Baiame Cave, Milbrodale, New South Wales

The exploits, activities and journeys of the Ancestors of the Dreaming created the Australian landscape and the country is now imbued with their spiritual essence. Your readings and activities for this week will raise your knowledge of the relationship between the Ancestors of the Dreaming, people, ‘country’ and sacred sites and how this relationship underlies Aboriginal cultures. From your study this week you will gain a deeper understanding of the impact of dispossession on Aboriginal peoples and the present struggle for land rights and Native Title as being more than reclamation of land as an economic base.

Elder of the Gagudgu Nation of Kakadu in the west of the Northern Territory, speaks of his relationship to country:

| “

|

Earth…

Like your father or brother or mother, because you were born from earth. You got to come back to earth. When you dead… you’ll come back to earth. Maybe little while yet… then you’ll come to earth. That’s your bone, your blood. It’s in this earth, same as for tree. I feel it with my body, with my blood. Feeling all these trees, all this country. When this wind blow you can feel it. Same for country… You can feel it. You can look, but feeling… that make you.

|

”

|

|

—Bill Neidjie (1985, p. 51)

|

The relationship to country and associated rights, obligations and duties with a particular site is inherited from a mother, father and/or conception and birth sites. The duties may include learning about a specific site and passing the knowledge on when it is time, or ensuring ceremonies are performed. A connection to specific areas determines obligations for caring for the land and everything on the land, including the people.

In defining the sacred nature of ‘country’, archaeologist and Aboriginal chaplain, states:

| “

|

The land is a sacred place, the locus of creative acts of the Dreaming, which persist into the present. It is still peopled by ancestral spirits who gave form to the landscape and its denizens and now rest at special places, the life centres. There, though dormant, they are yet conscious and active, releasing the spirit children and life force of their totem. It is not simply a landscape studded with discreet locations known as sacred sites. The whole is sacred with varying degrees of sacredness throughout, as if superimposed on the physical contours of the land; those who know can perceive spiritual contours (like our weather maps). Those who know, through totemic affiliation and initiation, have a mental map of their country, marking out where events of the Dreaming took place, criss-crossed by lines where the totemic ancestors travelled the sacred tracks between camps and places of significant happening, and highlighting their resting place and life centres.

|

”

|

|

—Father Eugene Stockton (1995, p. 56)

|

Key Idea

Aboriginal people are intimately identified with their country (land) and everything that is on that land.

Reflection

View this map of Australia.

What the map attempts to do:

The map represents research carried out for the Encyclopaedia of Aboriginal Australia (Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, 1994). This publication contains more detailed information than is available on the map.

The research method was to use the published resources available between 1988 and 1994. The map was then created as a graphic illustration. It indicates only the general location of larger groupings of people, which may include smaller groups such as clans, dialects or individual languages in a group.

What the map doesn’t attempt to do:

Dreaming stories are strongly connected with place. All life is interconnected with country; thus people are connected to the land, other people and all living things through the land.

The exploits, activities and journeys of the Ancestors of the Dreaming created the Australian landscape and the country is now imbued with their spiritual essence. Your readings and activities for this week will raise your knowledge of the relationship between the Ancestors of the Dreaming, people, ‘country’ and sacred sites and how this relationship underlies Aboriginal cultures. From your study this week you will gain a deeper understanding of the impact of dispossession on Aboriginal peoples and the present struggle for land rights and Native Title as being more than reclamation of land as an economic base.

Elder of the Gagudgu Nation of Kakadu in the west of the Northern Territory, speaks of his relationship to country:

Like your father or brother or mother, because you were born from earth. You got to come back to earth. When you dead… you’ll come back to earth. Maybe little while yet… then you’ll come to earth. That’s your bone, your blood. It’s in this earth, same as for tree. I feel it with my body, with my blood. Feeling all these trees, all this country. When this wind blow you can feel it. Same for country… You can feel it. You can look, but feeling… that make you.

—Bill Neidjie (1985, p. 51)

The relationship to country and associated rights, obligations and duties with a particular site is inherited from a mother, father and/or conception and birth sites. The duties may include learning about a specific site and passing the knowledge on when it is time, or ensuring ceremonies are performed. A connection to specific areas determines obligations for caring for the land and everything on the land, including the people.

In defining the sacred nature of ‘country’, archaeologist and Aboriginal chaplain, states:

—Father Eugene Stockton (1995, p. 56)

Content is available under the

Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike License.

Privacy Policy | Authors