An Introduction to Psychological Science

“Inside my head cropped”

Scientific research has been one of the great drivers of progress in human history, and the dramatic changes we have seen during the past century are due primarily to scientific findings—modern medicine, electronics, automobiles and jets, birth control, and a host of other helpful inventions. Psychologists believe that scientific methods can be used in the behavioural domain to understand and improve the world. For example:

- In clinical psychology, many studies have shown that cognitive behavioral therapy can help many people suffering from depression and anxiety disorders (Butler, Chapman, Forman, & Beck, 2006; Hoffman & Smits, 2008). In addition, research has also revealed that some types of therapies actually might be harmful on average (Lilienfeld, 2007).

- In organizational psychology, a number of psychological interventions have been found by researchers to produce greater productivity and satisfaction in the workplace (e.g., Yam, Fehr, & Barnes, 2014).

- Human factor engineers have greatly increased the safety and utility of the products we use. For example, the human factors psychologist Alphonse Chapanis and other researchers redesigned the cockpit controls of aircraft to make them less confusing and easier to respond to, and this led to a decrease in pilot errors and crashes (Chapanis, 2002).

- Although there have been many famous cases of imprisoned persons who have been exonerated because of DNA evidence, equally dramatic cases hinge on psychological findings. For instance, psychologist Elizabeth Loftus has conducted research demonstrating the limits and unreliability of eyewitness testimony and memory (e.g., Steblay & Loftus, 2013).

Thus, psychological findings are having practical importance in the world outside the laboratory. Psychological science has experienced enough success to demonstrate that it works, but there remains a huge amount yet to be learned.

Approaches to Knowledge

The study of knowledge, called epistemology, has identified four different approaches that people can use to arrive at their beliefs: common sense, appeal to an authority, personal insight, and the scientific method.

Common Sense

One approach to arriving at beliefs about our world is to rely on self‐evident or obvious particulars of our world and use these to derive additional understandings. However, our common sense often leads us to erroneous conclusions. For example, for a very long time common sense told people that the sun revolved around the earth.

Often the results of research agree with our common sense. For example, the degree of attraction between two people tends to increase as their physical similarity increases (Berkowitz, 1969). Common sense, as expressed in the proverb “birds of a feather flock together,” agrees with this research finding. Similarly, the number of ideas that someone can develop while working alone is doubled while working in a group (Osborn, 1957). This finding has also been expressed by a common‐sense proverb: two heads are better than one. However, understandings based on common sense are often neither precise nor consistent. The proverb “two heads are better than one” accounts for instances in which the work of a group is more efficient than the work of an individual. But common sense tells us that the opposite is true as well. Consider the proverb “too many cooks spoil the broth,” which suggests that having too many people work on task is problematic. For many common‐sense understandings expressed as proverbs, there exist other proverbs with roughly the opposite meaning. Table 1-1 provides some examples.

Table 1-1: Pairs of proverbs with opposite meanings

| Birds of a feather flock together.

|

Opposites attract.

|

| Too many cooks spoil the broth.

|

Two heads are better than one.

|

| Look before you leap.

|

He who hesitates is lost.

|

| Out of sight, out of mind.

|

Absence makes the heart grow fonder.

|

| A silent man is a wise one.

|

A man without words is a man without thoughts.

|

| Clothes make the man.

|

Don’t judge a book by its cover.

|

| Nothing ventured, nothing gained.

|

Better to be safe than sorry.

|

As general accounts of behaviour (what psychologists call theories), the two proverbs in any pair cannot both be true.

If problem solving sometimes works better with a group and sometimes with individual effort, additional factors must influence problem solving. The type and difficulty of the problem, and the skill and knowledge of the participants, could be other factors. Virtually all behaviour has more than one cause. This is why single-cause statements, such as proverbs, are inadequate as general accounts of behaviour.

In addition, sometimes research indicates that common beliefs are wrong. In general, people believe that their emotions are relatively apparent to those around them. Even when people might not want them to, they think that their emotions leak out. When people give speeches in public, they think that it is obvious to the audience that they are nervous. When people attempt to lie, they think that their guilty feelings are transparent. Researchers have labelled this the “illusion of transparency,” however, because one’s feelings are generally not obvious to others (Gilovich, Savitsky, & Medvec, 1998).

Appeal to Authority

An alternative approach to arriving at our beliefs is to rely on the expertise of authorities. We can appeal to doctors, lawyers, politicians, parents, religious leaders, scientists, or teachers to gain a better understanding of our world. However, this method has two major shortcomings: sometimes authorities deliberately mislead us because they have their own agendas (e.g., politicians, for self‐serving reasons, are sometimes “economical” with the truth) whereas at other times they are simply wrong (e.g., historically, the Catholic Church claimed that the earth was the centre of the universe and all the planets and stars orbited around it).

Personal Insight or Faith

Church shot during Easter 2009

An third approach to gaining an understanding of the world is based on personal insight. This might be the result of meditation, prayer, intuition, or even drugs. Like common sense and an appeal to authority, understandings based on faith are difficult to verify independently. For example, if you have a spiritual awakening that differs from your friend’s, and you both rely on faith alone, then it is not possible to determine if either of you has the correct understanding.

Similarly, if your belief based on common sense differs from a friend’s, or the authority you relied upon gave you a different answer than your friend’s authority gave him or her, then it is not possible to determine who is right by relying solely on using these methods.

Each of these first three approaches – common sense, appeals to authorities, and personal insight – is also limited in terms of the range of phenomena that they can address. For example, they are not particularly useful in understanding the neurochemicals that underlie cravings for specific foods. An alternative to these three approaches is the scientific approach, which is introduced in Chapter 1 of your textbook.

Scientific Method

When psychologists engage in research to increase their understanding of behaviour, they are putting into practice the principles of scientific thinking. Scientific thinking, like common sense, relies on observations of behaviour. But the scientific method involves additional factors. One of the most important aspects of the scientific method is that it involves external validation. A key component of external validation is replication, which means that If two researchers follow the same specified procedures in their experiment, then within a certain range of probabilities, they should achieve the same results. This is important because it means that when scientists disagree on results or are skeptical, they can repeat an experiment and see the results for themselves.

The scientific method, particularly as it relates to experiments, relies on manipulation and control. Manipulation refers to the systematic and planned difference between the groups whereas control refers to the elimination of differences (other than the manipulation), between the groups. For example, suppose you compared two groups of people to evaluate the effects of a new drug thought to promote weight loss. One group would get the drug and the other group would not (actually, experiments are typically much more complicated than this, involving many groups with many different drug dosages). Ideally, the presence or absence of the drug would be the only difference between the two groups. You would weigh the group members at the same time using the same scale, ensure they exercised and ate the same amount, and ensure they had the same expectations regarding their outcome in the study.

One of the most serious and prevalent of flaws in any experiment is the existence of confounds. Confounds exist when you compare groups that systematically differ in more than one way. For example, if the group that received the diet drug also exercised more, we would not know whether to attribute any weight loss to the effect of the drug or the exercise. A more detailed consideration of confounds is presented in Unit 4 after different research methods have been discussed.

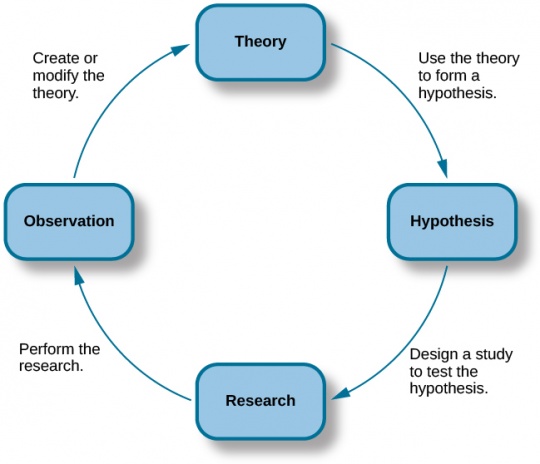

The Research Cycle

The starting point of psychological research is often the observation of behaviour. First you notice something and then you more carefully observe it. For example, you might notice that the price of stock for the Disney Corporation goes up and down.

The second step involves informed guessing, based on your observations, about the relationship between what you have observed and other variables. For example, you might note that during times of global unrest, the price of Disney stock increases. In other words, you may develop a tentative theory. This theory should explain the initial observations with a causal relationship and predict future observations.

The third step involves using the different scientific methods to test hypotheses (specific predictions) drawn from the theory in order to try to determine more exactly the nature of the relationship. At first, this might mean that you gather information about how strongly the two factors are related and in what direction (for example, as one factor increases, the other increases as well). For example, you conclude that during times of global unrest, people tend to shy away from travel to exotic locations and spend their discretionary money on entertainment or local travel (such as viewing Disney movies or going to Disneyland or Disney World), which are perceived as safer. Later, you might do experiments to determine if one factor causes the other to vary in a predictable way.

As evidence from these tests is collected and is consistent with the tentative theory, the researcher can claim greater confidence in the theory that generated the predictions. However, even if all the predictions are shown to be correct, this does not prove that the theory is correct. It may still be the case that some alternative theory does as well or better in accounting for past and future observations.

Usually, some of the predictions generated by the tentative theory will be disconfirmed; evidence from the experimental test will not be fully consistent with the experimental hypothesis. When this occurs, the researcher modifies the theory so that it no longer generates incorrect predictions. The modified theory will be stronger in the sense that it is consistent with a broader range of evidence. Confidence in a particular theory develops not only from showing that its predictions are confirmed but also from showing that alternative theories do a less adequate job of accounting for the evidence.

No doubt the revised theory and the observations on which it is based will yield more predictions, and so the cycles will continue. In fact, one criterion for choosing between alternative theories is their fertility (that is, their capacity to generate testable predictions).

Figure 1-1 depicts the cycle of research:

Figure 1-1: The scientific method of research includes proposing hypotheses, conducting research, and creating or modifying theories based on results

OpenStax College

Open Textbook Reading Activity

An Introduction to Psychological Science

Scientific research has been one of the great drivers of progress in human history, and the dramatic changes we have seen during the past century are due primarily to scientific findings—modern medicine, electronics, automobiles and jets, birth control, and a host of other helpful inventions. Psychologists believe that scientific methods can be used in the behavioural domain to understand and improve the world. For example:

Thus, psychological findings are having practical importance in the world outside the laboratory. Psychological science has experienced enough success to demonstrate that it works, but there remains a huge amount yet to be learned.

Approaches to Knowledge

The study of knowledge, called epistemology, has identified four different approaches that people can use to arrive at their beliefs: common sense, appeal to an authority, personal insight, and the scientific method.

Common Sense

One approach to arriving at beliefs about our world is to rely on self‐evident or obvious particulars of our world and use these to derive additional understandings. However, our common sense often leads us to erroneous conclusions. For example, for a very long time common sense told people that the sun revolved around the earth.

Often the results of research agree with our common sense. For example, the degree of attraction between two people tends to increase as their physical similarity increases (Berkowitz, 1969). Common sense, as expressed in the proverb “birds of a feather flock together,” agrees with this research finding. Similarly, the number of ideas that someone can develop while working alone is doubled while working in a group (Osborn, 1957). This finding has also been expressed by a common‐sense proverb: two heads are better than one. However, understandings based on common sense are often neither precise nor consistent. The proverb “two heads are better than one” accounts for instances in which the work of a group is more efficient than the work of an individual. But common sense tells us that the opposite is true as well. Consider the proverb “too many cooks spoil the broth,” which suggests that having too many people work on task is problematic. For many common‐sense understandings expressed as proverbs, there exist other proverbs with roughly the opposite meaning. Table 1-1 provides some examples.

Table 1-1: Pairs of proverbs with opposite meanings

As general accounts of behaviour (what psychologists call theories), the two proverbs in any pair cannot both be true.

If problem solving sometimes works better with a group and sometimes with individual effort, additional factors must influence problem solving. The type and difficulty of the problem, and the skill and knowledge of the participants, could be other factors. Virtually all behaviour has more than one cause. This is why single-cause statements, such as proverbs, are inadequate as general accounts of behaviour.

In addition, sometimes research indicates that common beliefs are wrong. In general, people believe that their emotions are relatively apparent to those around them. Even when people might not want them to, they think that their emotions leak out. When people give speeches in public, they think that it is obvious to the audience that they are nervous. When people attempt to lie, they think that their guilty feelings are transparent. Researchers have labelled this the “illusion of transparency,” however, because one’s feelings are generally not obvious to others (Gilovich, Savitsky, & Medvec, 1998).

Appeal to Authority

An alternative approach to arriving at our beliefs is to rely on the expertise of authorities. We can appeal to doctors, lawyers, politicians, parents, religious leaders, scientists, or teachers to gain a better understanding of our world. However, this method has two major shortcomings: sometimes authorities deliberately mislead us because they have their own agendas (e.g., politicians, for self‐serving reasons, are sometimes “economical” with the truth) whereas at other times they are simply wrong (e.g., historically, the Catholic Church claimed that the earth was the centre of the universe and all the planets and stars orbited around it).

Personal Insight or Faith

An third approach to gaining an understanding of the world is based on personal insight. This might be the result of meditation, prayer, intuition, or even drugs. Like common sense and an appeal to authority, understandings based on faith are difficult to verify independently. For example, if you have a spiritual awakening that differs from your friend’s, and you both rely on faith alone, then it is not possible to determine if either of you has the correct understanding.

Similarly, if your belief based on common sense differs from a friend’s, or the authority you relied upon gave you a different answer than your friend’s authority gave him or her, then it is not possible to determine who is right by relying solely on using these methods.

Each of these first three approaches – common sense, appeals to authorities, and personal insight – is also limited in terms of the range of phenomena that they can address. For example, they are not particularly useful in understanding the neurochemicals that underlie cravings for specific foods. An alternative to these three approaches is the scientific approach, which is introduced in Chapter 1 of your textbook.

Scientific Method

When psychologists engage in research to increase their understanding of behaviour, they are putting into practice the principles of scientific thinking. Scientific thinking, like common sense, relies on observations of behaviour. But the scientific method involves additional factors. One of the most important aspects of the scientific method is that it involves external validation. A key component of external validation is replication, which means that If two researchers follow the same specified procedures in their experiment, then within a certain range of probabilities, they should achieve the same results. This is important because it means that when scientists disagree on results or are skeptical, they can repeat an experiment and see the results for themselves.

The scientific method, particularly as it relates to experiments, relies on manipulation and control. Manipulation refers to the systematic and planned difference between the groups whereas control refers to the elimination of differences (other than the manipulation), between the groups. For example, suppose you compared two groups of people to evaluate the effects of a new drug thought to promote weight loss. One group would get the drug and the other group would not (actually, experiments are typically much more complicated than this, involving many groups with many different drug dosages). Ideally, the presence or absence of the drug would be the only difference between the two groups. You would weigh the group members at the same time using the same scale, ensure they exercised and ate the same amount, and ensure they had the same expectations regarding their outcome in the study.

One of the most serious and prevalent of flaws in any experiment is the existence of confounds. Confounds exist when you compare groups that systematically differ in more than one way. For example, if the group that received the diet drug also exercised more, we would not know whether to attribute any weight loss to the effect of the drug or the exercise. A more detailed consideration of confounds is presented in Unit 4 after different research methods have been discussed.

The Research Cycle

The starting point of psychological research is often the observation of behaviour. First you notice something and then you more carefully observe it. For example, you might notice that the price of stock for the Disney Corporation goes up and down.

The second step involves informed guessing, based on your observations, about the relationship between what you have observed and other variables. For example, you might note that during times of global unrest, the price of Disney stock increases. In other words, you may develop a tentative theory. This theory should explain the initial observations with a causal relationship and predict future observations.

The third step involves using the different scientific methods to test hypotheses (specific predictions) drawn from the theory in order to try to determine more exactly the nature of the relationship. At first, this might mean that you gather information about how strongly the two factors are related and in what direction (for example, as one factor increases, the other increases as well). For example, you conclude that during times of global unrest, people tend to shy away from travel to exotic locations and spend their discretionary money on entertainment or local travel (such as viewing Disney movies or going to Disneyland or Disney World), which are perceived as safer. Later, you might do experiments to determine if one factor causes the other to vary in a predictable way.

As evidence from these tests is collected and is consistent with the tentative theory, the researcher can claim greater confidence in the theory that generated the predictions. However, even if all the predictions are shown to be correct, this does not prove that the theory is correct. It may still be the case that some alternative theory does as well or better in accounting for past and future observations.

Usually, some of the predictions generated by the tentative theory will be disconfirmed; evidence from the experimental test will not be fully consistent with the experimental hypothesis. When this occurs, the researcher modifies the theory so that it no longer generates incorrect predictions. The modified theory will be stronger in the sense that it is consistent with a broader range of evidence. Confidence in a particular theory develops not only from showing that its predictions are confirmed but also from showing that alternative theories do a less adequate job of accounting for the evidence.

No doubt the revised theory and the observations on which it is based will yield more predictions, and so the cycles will continue. In fact, one criterion for choosing between alternative theories is their fertility (that is, their capacity to generate testable predictions).

Figure 1-1 depicts the cycle of research:

OpenStax College

Open Textbook Reading Activity

Read Chapter 1 of your textbook (The Science of Psychology). As you read this chapter consider how you typically gain and test your beliefs about the world. Also take the time to attempt each of the “Exercises” listed at the end of each page in your textbook.

Activity

Watch the video “Not all scientific studies are created equal” by David H. Schwartz. Once you are done, click on “Think” and attempt to answer the questions that appear on the screen.

Content is available under the

Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike License.

Privacy Policy | Authors