Although Indigenous Australians largely abandoned armed resistance to European occupation by the twentieth century, they continued to resist and developed new methods of fighting for their rights.

The 1920s and 1930s

The Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association (AAPA)

As John Maynard notes (in the one of the set readings for this week) by the 1920s in NSW, ‘[the] large-scale revocation of independent Aboriginal reserve lands … and the brutality of taking Aboriginal children from their families were the galvanising issues that ignited Aboriginal political revolt’ (2005, p. 1). It was these issues that led to the formation of the Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association (AAPA) in 1925 ‘the first united politically Aboriginal activist group to form in Australia (Maynard, 2003, p.91). Within a year it had eleven branches and over 500 members. They agitated for the return of land, the abolition of Protection Board powers, a stop to the removal of children and a royal commission (Broome, 2010, p. 204). Although this group disbanded by the late 1920s, others soon emerged.

Dubbo and the Aborigines Progressive Association

Dubbo was a hot bed of Aboriginal political activism from at least the 1920s. One of the most significant Aboriginal protest groups of the twentieth century, the Aborigines Progressive Association (APA), was founded in Dubbo in 1937. While white support was accepted, its membership was limited to Aboriginal people. In 1938 they started a newspaper (using language which would now be deemed offensive) The Abo Call to further their cause.

This declared that:

| “

|

“The Abo Call” is our own paper.

It has been established to present the case for aborigines, from the point of view of the Aborigines themselves.

This paper has nothing to do with missionaries, or anthropologists, or with anybody who looks down on Aborigines as an “Inferior” race.

We are NOT an inferior race, we have merely been refused the chance of education that whites receive. “The Abo Call” will show that we do not want to go back to the stone Age.

Representing 60,000 Full Bloods and 20,000 Halfcastes in Australia, we raise our voice to ask for education, Equal Opportunity, and Full Citizen Rights.Abo Call, no. 1, April 1938

|

”

|

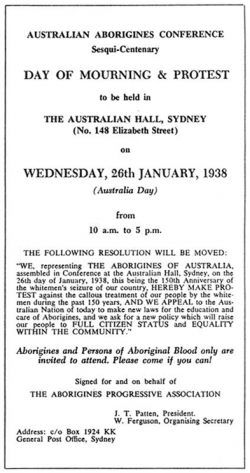

Day of Mourning & Protest Pamphlet.

The group soon formed other branches, and made connections with the Australian Aborigines’ League in Melbourne. Many famous Aboriginal leaders were associated with the APA – including William Ferguson (one of the key founders of the APA), Jack Patten, Bill Onus, William Cooper and Pearl Gibbs.

One of the APA’s first major initiatives was to organise the ‘Day of Mourning’ protest and conference in Sydney on Australia Day 1938 (the 150th anniversary of the arrival of the first fleet). Jack Patten and William Ferguson wrote a pamphlet, Aborigines Claim Citizen Rights! (Sydney: The Publicist, 1937) to explain the reasons for this protest.

| “

|

The 26th of January, 1938, is not a day of rejoicing for Australia’s Aborigines; it is a day of mourning. This festival of 150 years’ so-called “progress” in Australia commemorates also 150 years of misery and degradation imposed upon the original native inhabitants by the white invaders of this country … You are the New Australians, but we are the Old Australians. We have in our arteries the blood of the Original Australians, who have lived in this land for many thousands of years. You came here only recently, and you took our land away from us by force …

|

”

|

The Aboriginal Protection Board, which has “protected” the full-bloods of New South Wales so well that there are now less than a thousand of them remaining, has thus recently acquired the power to extend a similar “protection” to half-castes, quartercastes, and even to persons with any “admixture” of Aboriginal blood whatever. Its powers are so drastic that merely on suspicion or averment it can continue its persecuting protection unto the third, fourth and fifth generation of those so innocently unfortunate as to be descended from the original owners of this land.

In January 1938, following the Day of Mourning Protest, they sent a deputation to the Prime Minister, Joseph Lyons, outlining ‘Ten Points’ for change, which included calls for equal wages, education, health and housing.

Read some of Aboriginal Elder Uncle Ray Peckham recollections about the APA.

Uncle Ray is now the Elder in Residence at CSU.

Post WWII movements

The Pilbara Strikes, the Yirrkala Bark Petitions and the Wave Hill walk-off: Equal Pay and Land Rights

Prior to the 1960s large numbers of Aboriginal people worked on outback sheep and cattle stations. They were often paid only in rations, clothing and shelter. Sometimes this was supplemented by small cash payments. Often, such work provided a means for Aboriginal people to remain on their own country, and many developed a sense of pride and agency through work. But equally the conditions of their employment were highly exploitative, and the housing and food provided were extremely basic. The ‘cheap labour’ supplied by Aboriginal people to the pastoral industries was essential to their development (no other labour was available). Aboriginal people thus contributed enormously to the economic foundations of the Australian nation. But they received few financial benefits for their vital labour. (McGrath, 1987; Broome, 2010, pp. 122-48)

In 1946, Aboriginal pastoral workers in the Pilbara region of Western Australia began the first major campaigns for equal pay. Workers at 22 stations went on strike and the dispute continued for three years. Eventually the employers gave in. The Aboriginal workers were awarded better pay and conditions, but still not equal pay (Broome, 2010, pp. 141-43).

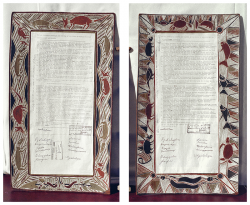

Yirrkala Bark Petition. Natural ochres on bark, ink on paper. House of Representatives, Canberra

Source

In 1965 the Conciliation and Arbitration Commission began considering a test case brought forward by the Australian Workers Union for equal pay for Aboriginal pastoral workers in the Northern Territory. The follow year equal wages were awarded – to take effect from 1968. This apparent victory, however, proved to have mixed outcomes. Now that Aboriginal workers were more expensive, the white owners of the pastoral stations switched to employing white workers. Indigenous families and whole communities were thus turned off properties where they had worked for generations (Taffe, 2008a).

Other important protests were also emerging around the issue of land rights in the 1960s. In 1963 the Yolngu community of Yirrkala in Arnhem Land sent two petitions to the Australian federal government to protest against the mining rights which the government had recently granted to several overseas companies to prospect for Bauxite on the Gove Peninsula where Yirrkala is located. The community were incensed that they had not been consulted, that they were not to receive any benefits from these mining rights, and more fundamentally that the government could actually give their land away in such a manner. The petitions were written on bark paper and contained painted designs proclaiming Yolngu law, depicting the traditional relations to land as well as typed text in both English and Gumatj languages. These petitions from the Yolngu people of Yirrkala were the first traditional documents recognised by the Commonwealth Parliament and are thus the documentary recognition of Indigenous people in Australian law (AIATSIS, 2013; Commonwealth of Australia, 2011: Broome, 227-37).

Their petition stated that this land had been ‘hunting and food gathering land for the Yirrkala tribes from time immemorial’. They were seeking government recognition of their rights to this land and asked that a government inquiry be held to investigate. When their appeals to Parliament failed Yolngu leaders turned to the Supreme Court in the Northern Territory, where hearings in their case, known as the Gove Land Rights Case, began in 1968. This case also failed. In handing down his decision in 1971, the judge accepted that Yolgnu had been living at Yirrkala for tens of thousands of years and that their law was based on intricate relations to land. He held, however, that Australian law could not recognise these as property relations and that this law as it stood could not solve the problem at the heart of the case: that the facts of Australian history disproved the ‘legal fiction’ of terra nullius, on which Australian law was built (AIATSIS, 2013; Commonwealth of Australia, 2011; Broome, 227-37).

This was not the only protest occurring at this time. In August 1966, Aboriginal pastoral workers walked off the job on the vast Vesteys’ cattle station at Wave Hill in the Northern Territory. The station was on Gurindji land. Their strike lasted over seven years. Led by Vincent Lingiari at first they expressed their unhappiness with their poor working conditions and disrespectful treatment. It thought at first that the protest was simply about wages, and the delayed implementation of equal pay. But it soon became clear that it was a wider protest. The striking workers wanted the return of their land. In 1967 they sent a petition to the Australian Governor General which stated, ‘we feel that morally the land is ours and should be returned to us'(cited in Taffe, 2008b). Along with the earlier Yirrkala Bark Petition, the walkout set in motion the modern land rights movement.

In 1975 the federal government intervened to broker a settlement and convinced the Vesteys to return part of the station to the Gurindji. The Prime Minister, Gough Whitlam, travelled to the Northern Territory and handed the deeds to 3300 square kilometre of Gurindji land to Vincent Lingiari. The next year, following on from the Recommendations of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Land Rights, the Federal Government passed the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act, 1976. (Broome, 227-37; Taffe, 2008b).

Now, around 50% of the land in the Northern Territory and 85% of its coastline are owned communally by Indigenous peoples.

Further Reading/Viewing/Listening

Aboriginal Tent Embassy

The 1967 Referendum and the Tent Embassy: From FCAATSI to Black Power

In 1958, representatives from various Aboriginal groups across the country met in Adelaide to discuss forming a national organisation which would unite existing state bodies to press for greater Commonwealth involvement in Aboriginal affairs and to work for the removal of discriminatory state legislation. They formed a Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders (FCAATSI). Although there were some Aboriginal people in this group, its leadership was predominantly white. The group campaigned on a wide array of issues, but soon focussed on one key objective – a referendum to change the Australian Constitution. This campaign was a great success (Taffe, 2005).

In May 1967, Australian voters were asked to vote in a referendum to determine whether two references in the Australian Constitution, which discriminated against Aboriginal people, should be removed. The first reference was section 51, which stated that:

| “

|

The Parliament shall, have the power to make laws for the peace, order, and good government of the Commonwealth with respect to, clause xxvi, that the people of any race, other than the Aboriginal people in any State, for whom it is necessary to make special laws.

The second was section 127, which stated that:

In reckoning the numbers of the people of the Commonwealth, or of a State or other part of the Commonwealth, Aboriginal natives should not be counted.

|

”

|

Over 90 per cent of Australians voted ‘Yes’ in favour of removing the words, ‘other than the aboriginal people in any State’ in section 51(xxvi) and the whole of section 127.

It was hoped that these changes would bring about an end to state-based discriminatory legislation, and allow the Commonwealth government to enacted legislation to restore Aboriginal rights (Attwood and Markus, 2007).

Voting Rights and Citizenship

It is widely but wrongly believed that the 1967 referendum gave Aboriginal people Australian citizenship and that it gave them the right to vote in federal elections. Neither of these statements is correct. Aboriginal people became Australian citizens in 1949, when a separate Australian citizenship was created for the first time (before this, reflecting the nation’s past as a collection of British colonies, and the fact that the British monarch was all Australians, including Australian Indigenous peoples, were ‘British subjects’). Aboriginal people from Queensland and Western Australia gained the vote in Commonwealth elections in 1962. However, the Commonwealth voting right of Aborigines from other states was confirmed by a Commonwealth Act in 1949 (the constitution already gave them that right but it was often interpreted differently before 1949). They got the vote in WA state elections in 1962 and Queensland state elections in 1965 (Chesterman, 2005).

Black Power and the Tent Embassy

Corroboree for Sovereignty at the Aboriginal Tent Embassy

While there were certainly some improvements in Aboriginal rights by the early 1970s, there was still much dissatisfaction about key issues such as land rights. More radical politics emerged. This was illustrated by the split in FCAATSI in 1970. Growing Indigenous dissatisfaction about their lack of power in the organisation came to a head at the 1970 conference. Motions were put that voting power and executive positions should be limited to people of Aboriginal or Islander descent. Kath Walker (who would later change her name to Oodgeroo Noonuccal) had argued strongly and passionately for Indigenous people to take control of their own affairs. In 1973, FCAATSI did finally become an Indigenous-controlled organisation. But it disbanded by 1978 as other groups emerged. This split reflected emerging ideas about Black Power (influenced by movement in the US).

Late on Australia Day 1972, four young Aboriginal men erected a beach umbrella on the lawns outside Parliament House in Canberra and put up a sign which read ‘Aboriginal Embassy’. They were primarily motivated by the lack of progress being made on the issue of land rights. Over the following months, supporters of the embassy swelled to 2000. When the police violently dismantled the tents and television film crews captured the violence for the evening news, an outraged public expressed its disgust to the federal government. The site became known as the ‘Tent Embassy’ and it remains on the lawns of Old Parliament House in Canberra to this day.

National Museum Australia. Collaborating for Indigenous Rights.

I would strong recommend that you also look at some of the primary documents contained in this book, most written by Aboriginal activists. Please also note that this text uses terminology which would now be deemed inappropriate, especially the use of Aborigine/s throughout. Please do not imitate this language in your own writing.

- Why might Indigenous Australians have had such an ongoing struggle to have their human rights recognised?

- What does it say about the strength of Aboriginal communities and their survival?

Key Idea

Although Indigenous Australians largely abandoned armed resistance to European occupation by the twentieth century, they continued to resist and developed new methods of fighting for their rights.

The 1920s and 1930s

The Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association (AAPA)

As John Maynard notes (in the one of the set readings for this week) by the 1920s in NSW, ‘[the] large-scale revocation of independent Aboriginal reserve lands … and the brutality of taking Aboriginal children from their families were the galvanising issues that ignited Aboriginal political revolt’ (2005, p. 1). It was these issues that led to the formation of the Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association (AAPA) in 1925 ‘the first united politically Aboriginal activist group to form in Australia (Maynard, 2003, p.91). Within a year it had eleven branches and over 500 members. They agitated for the return of land, the abolition of Protection Board powers, a stop to the removal of children and a royal commission (Broome, 2010, p. 204). Although this group disbanded by the late 1920s, others soon emerged.

Dubbo and the Aborigines Progressive Association

Dubbo was a hot bed of Aboriginal political activism from at least the 1920s. One of the most significant Aboriginal protest groups of the twentieth century, the Aborigines Progressive Association (APA), was founded in Dubbo in 1937. While white support was accepted, its membership was limited to Aboriginal people. In 1938 they started a newspaper (using language which would now be deemed offensive) The Abo Call to further their cause.

This declared that:

It has been established to present the case for aborigines, from the point of view of the Aborigines themselves.

This paper has nothing to do with missionaries, or anthropologists, or with anybody who looks down on Aborigines as an “Inferior” race.

We are NOT an inferior race, we have merely been refused the chance of education that whites receive. “The Abo Call” will show that we do not want to go back to the stone Age.

Representing 60,000 Full Bloods and 20,000 Halfcastes in Australia, we raise our voice to ask for education, Equal Opportunity, and Full Citizen Rights.Abo Call, no. 1, April 1938

The group soon formed other branches, and made connections with the Australian Aborigines’ League in Melbourne. Many famous Aboriginal leaders were associated with the APA – including William Ferguson (one of the key founders of the APA), Jack Patten, Bill Onus, William Cooper and Pearl Gibbs.

One of the APA’s first major initiatives was to organise the ‘Day of Mourning’ protest and conference in Sydney on Australia Day 1938 (the 150th anniversary of the arrival of the first fleet). Jack Patten and William Ferguson wrote a pamphlet, Aborigines Claim Citizen Rights! (Sydney: The Publicist, 1937) to explain the reasons for this protest.

The Aboriginal Protection Board, which has “protected” the full-bloods of New South Wales so well that there are now less than a thousand of them remaining, has thus recently acquired the power to extend a similar “protection” to half-castes, quartercastes, and even to persons with any “admixture” of Aboriginal blood whatever. Its powers are so drastic that merely on suspicion or averment it can continue its persecuting protection unto the third, fourth and fifth generation of those so innocently unfortunate as to be descended from the original owners of this land.

In January 1938, following the Day of Mourning Protest, they sent a deputation to the Prime Minister, Joseph Lyons, outlining ‘Ten Points’ for change, which included calls for equal wages, education, health and housing.

Read some of Aboriginal Elder Uncle Ray Peckham recollections about the APA.

Uncle Ray is now the Elder in Residence at CSU.

Post WWII movements

The Pilbara Strikes, the Yirrkala Bark Petitions and the Wave Hill walk-off: Equal Pay and Land Rights

Prior to the 1960s large numbers of Aboriginal people worked on outback sheep and cattle stations. They were often paid only in rations, clothing and shelter. Sometimes this was supplemented by small cash payments. Often, such work provided a means for Aboriginal people to remain on their own country, and many developed a sense of pride and agency through work. But equally the conditions of their employment were highly exploitative, and the housing and food provided were extremely basic. The ‘cheap labour’ supplied by Aboriginal people to the pastoral industries was essential to their development (no other labour was available). Aboriginal people thus contributed enormously to the economic foundations of the Australian nation. But they received few financial benefits for their vital labour. (McGrath, 1987; Broome, 2010, pp. 122-48)

In 1946, Aboriginal pastoral workers in the Pilbara region of Western Australia began the first major campaigns for equal pay. Workers at 22 stations went on strike and the dispute continued for three years. Eventually the employers gave in. The Aboriginal workers were awarded better pay and conditions, but still not equal pay (Broome, 2010, pp. 141-43).

In 1965 the Conciliation and Arbitration Commission began considering a test case brought forward by the Australian Workers Union for equal pay for Aboriginal pastoral workers in the Northern Territory. The follow year equal wages were awarded – to take effect from 1968. This apparent victory, however, proved to have mixed outcomes. Now that Aboriginal workers were more expensive, the white owners of the pastoral stations switched to employing white workers. Indigenous families and whole communities were thus turned off properties where they had worked for generations (Taffe, 2008a).

Other important protests were also emerging around the issue of land rights in the 1960s. In 1963 the Yolngu community of Yirrkala in Arnhem Land sent two petitions to the Australian federal government to protest against the mining rights which the government had recently granted to several overseas companies to prospect for Bauxite on the Gove Peninsula where Yirrkala is located. The community were incensed that they had not been consulted, that they were not to receive any benefits from these mining rights, and more fundamentally that the government could actually give their land away in such a manner. The petitions were written on bark paper and contained painted designs proclaiming Yolngu law, depicting the traditional relations to land as well as typed text in both English and Gumatj languages. These petitions from the Yolngu people of Yirrkala were the first traditional documents recognised by the Commonwealth Parliament and are thus the documentary recognition of Indigenous people in Australian law (AIATSIS, 2013; Commonwealth of Australia, 2011: Broome, 227-37).

Their petition stated that this land had been ‘hunting and food gathering land for the Yirrkala tribes from time immemorial’. They were seeking government recognition of their rights to this land and asked that a government inquiry be held to investigate. When their appeals to Parliament failed Yolngu leaders turned to the Supreme Court in the Northern Territory, where hearings in their case, known as the Gove Land Rights Case, began in 1968. This case also failed. In handing down his decision in 1971, the judge accepted that Yolgnu had been living at Yirrkala for tens of thousands of years and that their law was based on intricate relations to land. He held, however, that Australian law could not recognise these as property relations and that this law as it stood could not solve the problem at the heart of the case: that the facts of Australian history disproved the ‘legal fiction’ of terra nullius, on which Australian law was built (AIATSIS, 2013; Commonwealth of Australia, 2011; Broome, 227-37).

This was not the only protest occurring at this time. In August 1966, Aboriginal pastoral workers walked off the job on the vast Vesteys’ cattle station at Wave Hill in the Northern Territory. The station was on Gurindji land. Their strike lasted over seven years. Led by Vincent Lingiari at first they expressed their unhappiness with their poor working conditions and disrespectful treatment. It thought at first that the protest was simply about wages, and the delayed implementation of equal pay. But it soon became clear that it was a wider protest. The striking workers wanted the return of their land. In 1967 they sent a petition to the Australian Governor General which stated, ‘we feel that morally the land is ours and should be returned to us'(cited in Taffe, 2008b). Along with the earlier Yirrkala Bark Petition, the walkout set in motion the modern land rights movement.

In 1975 the federal government intervened to broker a settlement and convinced the Vesteys to return part of the station to the Gurindji. The Prime Minister, Gough Whitlam, travelled to the Northern Territory and handed the deeds to 3300 square kilometre of Gurindji land to Vincent Lingiari. The next year, following on from the Recommendations of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Land Rights, the Federal Government passed the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act, 1976. (Broome, 227-37; Taffe, 2008b).

Now, around 50% of the land in the Northern Territory and 85% of its coastline are owned communally by Indigenous peoples.

Further Reading/Viewing/Listening

The song, ‘From Little Things Big Things Grow,’ written by Kev Carmody with Paul Kelly in 1993 commemorates the Gurindji walkout from Wave Hill Station. You can listen to the song here.

See the National Museum of Australia’s website ‘Collaborating for Indigenous Rights’, developed by Dr. Sue Taffe, for more information about the protest.

See also resources at the National Archives of Australia: ‘The Wave Hill ‘walk-off’’ at:

You can watch an ABC television report on the strike, broadcast in 1968, (including an interview with Vincent Lingiari)

The 1967 Referendum and the Tent Embassy: From FCAATSI to Black Power

In 1958, representatives from various Aboriginal groups across the country met in Adelaide to discuss forming a national organisation which would unite existing state bodies to press for greater Commonwealth involvement in Aboriginal affairs and to work for the removal of discriminatory state legislation. They formed a Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders (FCAATSI). Although there were some Aboriginal people in this group, its leadership was predominantly white. The group campaigned on a wide array of issues, but soon focussed on one key objective – a referendum to change the Australian Constitution. This campaign was a great success (Taffe, 2005).

In May 1967, Australian voters were asked to vote in a referendum to determine whether two references in the Australian Constitution, which discriminated against Aboriginal people, should be removed. The first reference was section 51, which stated that:

The second was section 127, which stated that:

In reckoning the numbers of the people of the Commonwealth, or of a State or other part of the Commonwealth, Aboriginal natives should not be counted.

Over 90 per cent of Australians voted ‘Yes’ in favour of removing the words, ‘other than the aboriginal people in any State’ in section 51(xxvi) and the whole of section 127.

It was hoped that these changes would bring about an end to state-based discriminatory legislation, and allow the Commonwealth government to enacted legislation to restore Aboriginal rights (Attwood and Markus, 2007).

Voting Rights and Citizenship

It is widely but wrongly believed that the 1967 referendum gave Aboriginal people Australian citizenship and that it gave them the right to vote in federal elections. Neither of these statements is correct. Aboriginal people became Australian citizens in 1949, when a separate Australian citizenship was created for the first time (before this, reflecting the nation’s past as a collection of British colonies, and the fact that the British monarch was all Australians, including Australian Indigenous peoples, were ‘British subjects’). Aboriginal people from Queensland and Western Australia gained the vote in Commonwealth elections in 1962. However, the Commonwealth voting right of Aborigines from other states was confirmed by a Commonwealth Act in 1949 (the constitution already gave them that right but it was often interpreted differently before 1949). They got the vote in WA state elections in 1962 and Queensland state elections in 1965 (Chesterman, 2005).

Recommended Reading

National Archives of Australia The 1967 referendum – Fact sheet 150.

[NB: this site has some great links to primary sources on the referendum and links to other resources and to other topics – both within NAA and outside]

Black Power and the Tent Embassy

While there were certainly some improvements in Aboriginal rights by the early 1970s, there was still much dissatisfaction about key issues such as land rights. More radical politics emerged. This was illustrated by the split in FCAATSI in 1970. Growing Indigenous dissatisfaction about their lack of power in the organisation came to a head at the 1970 conference. Motions were put that voting power and executive positions should be limited to people of Aboriginal or Islander descent. Kath Walker (who would later change her name to Oodgeroo Noonuccal) had argued strongly and passionately for Indigenous people to take control of their own affairs. In 1973, FCAATSI did finally become an Indigenous-controlled organisation. But it disbanded by 1978 as other groups emerged. This split reflected emerging ideas about Black Power (influenced by movement in the US).

Late on Australia Day 1972, four young Aboriginal men erected a beach umbrella on the lawns outside Parliament House in Canberra and put up a sign which read ‘Aboriginal Embassy’. They were primarily motivated by the lack of progress being made on the issue of land rights. Over the following months, supporters of the embassy swelled to 2000. When the police violently dismantled the tents and television film crews captured the violence for the evening news, an outraged public expressed its disgust to the federal government. The site became known as the ‘Tent Embassy’ and it remains on the lawns of Old Parliament House in Canberra to this day.

Required Reading

National Museum Australia. Collaborating for Indigenous Rights.

I would strong recommend that you also look at some of the primary documents contained in this book, most written by Aboriginal activists. Please also note that this text uses terminology which would now be deemed inappropriate, especially the use of Aborigine/s throughout. Please do not imitate this language in your own writing.

Reflection

Content is available under the

Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike License.

Privacy Policy | Authors