Nature has been identified in art going back to the cave man. It starts to become prominent in the Italian Renaissance, especially Venice, where there was not a lot of landscape other than the sea. Constable brought landscape painting to the English in the 18th-century when he painted a countryside remembered before the land was divided up with hedgerows. Astronauts have commented how beautiful the earth looks from space and that we ought to appreciate where we live. There is something comforting about landscape the more we remove ourselves from it.

The natural world has always given artists subject matter to experience and interpret. In it we find some of our greatest fears, so we try to organize it. It gives us spectacular joy, so we mimic it. Its grandeur motivates some of our highest aspirations, so we spin it in myth and symbolism. Our relationship with nature presents ironies too: it’s referred to as a maternal force, yet advanced societies are the most removed from it. All of these characteristics of nature become the stuff of artistic expression.

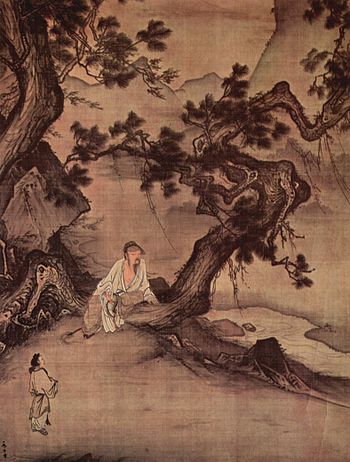

Ma Lin, Quietly Listening to Wind in the Pines, 1246. Ink on silk, National Palace Museum, Taiwan

Chinese culture includes a reverence for nature that’s reflected in its traditional painting styles. Landscape is used as metaphor to illustrate physical, philosophical and spiritual themes. We looked at Ma Lin’s wall scroll in the module “Artistic media: Two-dimensional art” in terms of the artist’s painting technique. Let’s reexamine it now to see how Lin creates subject matter that gives prominence to both nature and the figure. First of all, he animates the landscape to emphasize its scale and undulating features, contrasting large boulders and strong, twisted pines in the middle ground with a more subtly painted background of mountains and water. A figure (a wanderer, priest or poet) rests at the base of a pine, more in contemplation and unity with his surroundings than in opposition to them. Notice how this figure is painted with colored pigment that brings an emphasis to his place in the composition. A second, even smaller figure inhabits the foreground on the left, enhancing the landscape’s sense of scale.

In Loquats and Mountain Bird , the artist’s keen observational skills give specific information, but the work transcends mere physical description of the subject matter. Through formal composition and the artist’s deft touch we see a slice of nature – in a very shallow space, that is unified and completely believable. A similar but perhaps less poetic effect can be seen in the works of John James Audubon. Audubon spent years documenting the birds and animals in America during the first half of the nineteenth century. The shallow space and strong use of placement, color and pattern give a more dramatic edge to his images.

In another more contemporary example, the glasswork of Ginny Ruffner provides a whimsical approach to her experiences with the natural world, providing delicate visual comments like the simple pleasure of looking out a window (see 2009, Out My Window) or marveling at the cyclical rhythms of water.

The natural world and our own experiences within it are incorporated into more utilitarian forms of art too. Architecture, often seen as an inorganic structural component, can mimic the landscape surrounding it. The 15th century Inca site of Machu Picchu in Peru contains dwellings with pyramidal stonewalls rising like the nearby mountain the site is named for. In addition to the buildings being extremely stable, their design directly reflects the cultural importance given the entire area. Machu Picchu was the center of Inca civilization. The development included terraced farms, homes, industrial buildings and religious temples.

-

Machu Picchu, Peru, 15th century Inca civilization

-

Machu Picchu archeological site

Introduction to the Natural World

Nature has been identified in art going back to the cave man. It starts to become prominent in the Italian Renaissance, especially Venice, where there was not a lot of landscape other than the sea. Constable brought landscape painting to the English in the 18th-century when he painted a countryside remembered before the land was divided up with hedgerows. Astronauts have commented how beautiful the earth looks from space and that we ought to appreciate where we live. There is something comforting about landscape the more we remove ourselves from it.

The natural world has always given artists subject matter to experience and interpret. In it we find some of our greatest fears, so we try to organize it. It gives us spectacular joy, so we mimic it. Its grandeur motivates some of our highest aspirations, so we spin it in myth and symbolism. Our relationship with nature presents ironies too: it’s referred to as a maternal force, yet advanced societies are the most removed from it. All of these characteristics of nature become the stuff of artistic expression.

Chinese culture includes a reverence for nature that’s reflected in its traditional painting styles. Landscape is used as metaphor to illustrate physical, philosophical and spiritual themes. We looked at Ma Lin’s wall scroll in the module “Artistic media: Two-dimensional art” in terms of the artist’s painting technique. Let’s reexamine it now to see how Lin creates subject matter that gives prominence to both nature and the figure. First of all, he animates the landscape to emphasize its scale and undulating features, contrasting large boulders and strong, twisted pines in the middle ground with a more subtly painted background of mountains and water. A figure (a wanderer, priest or poet) rests at the base of a pine, more in contemplation and unity with his surroundings than in opposition to them. Notice how this figure is painted with colored pigment that brings an emphasis to his place in the composition. A second, even smaller figure inhabits the foreground on the left, enhancing the landscape’s sense of scale.

In Loquats and Mountain Bird , the artist’s keen observational skills give specific information, but the work transcends mere physical description of the subject matter. Through formal composition and the artist’s deft touch we see a slice of nature – in a very shallow space, that is unified and completely believable. A similar but perhaps less poetic effect can be seen in the works of John James Audubon. Audubon spent years documenting the birds and animals in America during the first half of the nineteenth century. The shallow space and strong use of placement, color and pattern give a more dramatic edge to his images.

In another more contemporary example, the glasswork of Ginny Ruffner provides a whimsical approach to her experiences with the natural world, providing delicate visual comments like the simple pleasure of looking out a window (see 2009, Out My Window) or marveling at the cyclical rhythms of water.

The natural world and our own experiences within it are incorporated into more utilitarian forms of art too. Architecture, often seen as an inorganic structural component, can mimic the landscape surrounding it. The 15th century Inca site of Machu Picchu in Peru contains dwellings with pyramidal stonewalls rising like the nearby mountain the site is named for. In addition to the buildings being extremely stable, their design directly reflects the cultural importance given the entire area. Machu Picchu was the center of Inca civilization. The development included terraced farms, homes, industrial buildings and religious temples.

Machu Picchu, Peru, 15th century Inca civilization

Machu Picchu archeological site

Nature and Technology

Look at Chris Jordan’s digital images. Referring to images from his various themes such as Midway, Running the Numbers, Intolerable Beauty and In Katrina’s Wake, describe in your private learning journal how you think his work reflects the ideas about nature, knowledge and technology. In addition, make a comment about the aesthetic nature of his work.

In the course feed, answer one of the following questions:

Be specific in your answers. Give additional examples or references if you want.

You must be logged in to post to WEnotes.

Note: Your comment will be displayed in the course feed.

Content is available under the

Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike License.

Privacy Policy | Authors