| “

|

They hang the man and flog the woman

Who steals the goose from off the common

But leave the greater villain loose

Who steals the common from off the goose.

|

”

|

|

—Anonymous protest poem, 1764 or 1821

|

Orientation

Indicate whether the following statements are true or false:

- The origins of plagiarism can be traced to society’s moral conviction that it is wrong to copy someone’s work

- True

- Incorrect. The notion of plagiarism did not exist prior to the inception of copyright. Only since the introduction of copyright did it become legally and socially unaceptable to copy without attributing the author.

- False

- Correct. Plagiarism is more of a historical construct than a moral issue, albeit that today we consider the act of copying to be ethically questionable in the absence of attributing the original author.

- Copyright was first introduced to protect the rights of the copyright holder.

- True

- Incorrect. Copyright was originally introduced to restrict the rights of the copyright holder.

- False

- Correct. The concept of copyright was introduced as the “Act for the Encouragement of Learning” thus promoting the right to copy.

Copyright: A foreign concept to the ancient mind

Portrait of Aristotle. “

Imitation is natural to man from childhood [and] the first things that he learns come to him through imitation.“

[1]

Copyright in the common law countries (British legal heritage) began officially in the eighteenth century. Prior to that, ancient scribes (the earliest copiers) in writing the classics and sacred books of different religions were quite comfortable in excluding, substituting, amending, expanding, and abridging their materials. In the fourth century BC, Aristotle wrote:

| “

|

Imitation is natural to man from childhood [and] the first things that he learns come to him through imitation.[1]

|

”

|

The ancients had no proscriptions against copying or what we conceive today as plagiarism. Our ancestors’ understanding of the world was housed in stories – not dogma. Storytellers had no “moral” right to protect their tales. No one questioned the right of anyone to copy these and other works. “The concept of copyright was utterly foreign to the ancient mind”.[2]

Going to war for the right to copy a book

In Ireland in the sixth century there occurred the earliest known judgment on the right to copy. An Irish monk, Columcille, copied without permission St. Jerome’s psalter, a hymn book belonging to St. Finnian, the abbot of another monastery. Finnian asked Columcille to return the copy of the book claiming it to be stolen property and was refused. Finnian appealed to the High King of Ireland, King Diarmait, who pronounced the judgement in Finnian’s favour: “To every cow its calf to every book its copy.” Columcille responded to this adverse judgement with force and met the king’s men in battle at Cuildremne in 561. Columcille was triumphant and King Diarmait was exiled from Ireland, but as a result more than 3 000 men lay dead.[3] Columcille was later also exiled to Scotland, where he is known as St. Columba.[4] It could be said that although he lost the court case, with the battle, he won his point. This battle resolved the copyright issue in favour of openness for more than a millennium. The Irish monks continued copying books, spread out from Scotland, and brought the enlightenment to Europe.[5]

Many authors but only a few presses: An early distribution monopoly

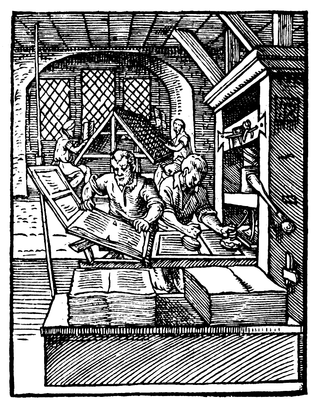

This

woodcut from 1568 depicts an early printing press capable of printing around 3600 pages per day.

The printing press, with its capacity to mass produce copies, came to Europe in the 15th century. There were few presses and many authors, so the printers gained control over the books that were produced, usually by paying authors a one-time fee. Monarchs found it easier to tax and control the few printers than tax all the authors, so they granted them monopolistic rights in return for taxes and censorship. The Stationers Company, which was made up of members of a printing guild, was granted a printing monopoly in 1557 in order to prevent the spread of Protestant writing in England.[6] During the Cromwellian period, the print monopolies were strengthened although the censorship was then directed against opponents of Puritanism.

It is during this period that copying without referencing the author became socially unacceptable. Ben Johnson was one of the first authors to use the term “plagiary” in English with its current meaning. The Oxford English Dictionary provides an earlier reference from Montagu in 1621, who used the word “plagiarisme” in the sense of purloining someone’s work.[7] Howard argues, therefore, that plagiarism is a historical construction rather than a moral category.[8] Downes acknowledges that plagiarism, while being mendacious, is not theft. Rather it is “a breach of trust between the plagiarizer and the reader . . . a misrepresentation of one’s self as something one is not.”[9]

Origins of copyright

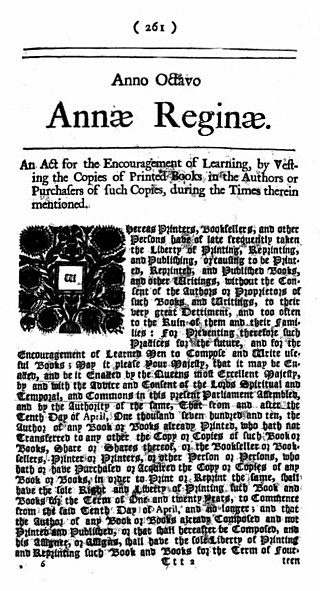

The Statute of Anne, “An Act for the Encouragement of Learning”, enacted in 1709.

Our modern concept of copyright in British common law has developed from the Statute of Queen Anne 1710 An Act for the Encouragement of Learning. It was passed for the purpose of promoting learning, specifically to encourage “learned men to compose and write useful books”.[10] Up until then, the publishers could pass on their royal grants of copyright to their heirs in perpetuity. This Act was a consequence of the 1707 Act of Union with Scotland to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain. Scottish booksellers would not accept the English monopoly of the London Stationers’ Company. This first copyright law had the purpose of breaking the Stationers’ monopoly and so, it was not a mechanism for protecting copyright controller’s rights as it is often portrayed nowadays. A number of features of the Act served the interests of the general public, for instance[11]:

- The limitation of the duration of the controllers’ rights (previously indefinite) thus ensuring that works would enter the public domain.

- The requirement for copies of books to be placed in university libraries thus ensuring public access to copyrighted works.

Therefore, copyright law was expressly introduced to limit the rights of the previous monopoly of control.

In the Statute of Queen Anne, copyright was wrested from the printers and vested in the authors. This right was limited to a maximum of 28 years, after which works entered the public domain. So in effect, this statute created the public domain – the intellectual commons. This is the most important aspect of this law for the public and for education. It created a body of works that could be copied, altered, adapted, or tweaked by anyone for amusement, profit, or enlightenment. In addition, Article IX gave a special exemption to universities to ensure that none of their traditional copying rights were affected. This was no coincidence, intellectuals like John Locke actively campaigned for the repeal of the monopoly in the book trade and strongly condemned the restrictions on science caused by the monopolies of the Stationers Company.[12]

Copyright Act of 1790 for the Encouragement of Learning in the Colombian Centinel

Forté explains: “Copyright isn’t on a par with the right to life, liberty, fraternity and equality before the law. It’s a privilege extended to us by our fellow citizens because they recognise the value they get out of our efforts.”[13] Copyright was never intended to be primarily a vehicle for protecting the rights of the copyright holders. On the contrary, copyright was initiated specifically to promote learning by removing the perpetual rights of the copyright controllers transferring the rights to the authors and imposing a reasonable time limit on their privilege.

Most of the colonies that formed the United States had laws that were based on the Statute of Queen Anne.[14] So it is not co-incidental that the U.S. Constitution echoes this purpose. It specifically refers to Congress’s duty in Article I Section 8:

| “

|

To promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries.[15]

|

”

|

This was followed by the Copyright Act 1790: An Act for the Encouragement of Learning and it was signed by George Washington.[16] Like the Statute of Queen Anne, this act (as the title suggests) was enacted specifically for the “encouragement of learning” and is meant to protect the rights of copyright holders only insofar as it serves that purpose. Thomas Jefferson expressly opposed linking copy rights to property rights, writing in 1813: “Inventions then cannot, in nature, be a subject of property.”[17] President Madison wrote: “…incentive, not property, or natural law is the foundational justification for American copyright.”[18]

Thus the origin of copyright suggests that there is no common law support for intellectual property. It is a privileged monopoly, not a right. Since these laws were first enacted, the copyright controllers have successfully waged a continuous war aiming to extend their rights at the expense of education and the general public, morphing the meaning of copyright in the public’s mind to become “intellectual property.”

Note that other countries have different traditions. For example most of continental Europe, Francophone Africa and Latin America follow the Napoleonic Code, which is based on “droit d’auteur” (author’s rights). Indigenous copyright too follows varied customs and traditions.

Closing reflection

In “Stealing the goose: Copyright and learning” (from which this page was adapted) Rory McGreal concludes:

| “

|

Copyright law was expressly introduced to limit the rights of the controllers and distributors of knowledge. Yet, these controllers are successfully turning a “copy” right into a property right. The traditional rights of learning institutions are being taken away. The balance for researchers should be restored. Research and learning must be allowed the broad interpretation that was intended in the original laws.[19]

|

”

|

Fortunately, in a digital world, Creative Commons provides the legal tools for education institutions to restore some of the balance by granting permissions and freedom to create new knowledge with fewer restrictions.

Do you agree with this position?

Share with us your thoughts about the development of copyright. Post your contribution on WENotes. Below are two questions to get you thinking. You might respond In my opinion…. .

- Should the rights of authors to “own” their creative works supercede that of research and learning, especially in light of the internet’s broad use as an educational tool? Why?

- Do you believe the right of an author to “own” his/her creative work is a property right? Why?

You must be logged in to post to WEnotes.

Note: Your comment will be displayed in the course feed.

Further reading

We recommend the following sources for further reading:

Acknowledgements

This subsection was adapted from:

McGreal, R. (2004). Stealing the goose: Copyright and learning. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 5(3). Retrieved from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/205

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Aristotle. (2004, April). The Poetics. Retrieved 9 September 2004.

- ↑ Harpur, T. (2004). The Pagan Christ: Recovering the Lost Light. Toronto: Thomas Allen. p. 14.

- ↑ Thomas, J. B. (2004). St. Columba. The Catholic Encyclopedia, Volume IV. Retrieved 25 March 2004.

- ↑ Concannon, K. (2004, July 1). St. Columcille: Ireland’s first ‘White Martyr’. Catholic Herald. Retrieved 20 August 2004.

- ↑ Cahill, T. (1995). How the Irish saved civilization: The untold story of Ireland’s heroic role from the fall of Rome to the rise of medieval Europe (Vol. I). New York: Doubleday.

- ↑ Editors. (2004, August). Stationers Company. Literary Encyclopedia. Retrieved 7 September 2004.

- ↑ Oxford University Press. (n.d.). Oxford English Dictionary: plagiarize. Retrieved 9 September 2004.

- ↑ Howard, R. M. (1988). Review of Mallon, Thomas. Stolen Words: Forays into the origins and ravages of plagiarism. New York: Ticknor and Fields, 1989. Retrieved 9 September 2004.

- ↑ Downes, S. (2003, April). Copyright, ethics and theft. Journal of the United States Distance Learning Association, 17(2). Retrieved 13 May 2003.

- ↑ House of Commons. (1709). An Act for the Encouragement of Learning, by Vesting the Copies of Printed Books in the Author’s or Purchasers of Such Copies. Retrieved 28 October 2003.

- ↑ Rimmer, M. (2007). Digital copyright and the consumer revolution: hands off my iPod. Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 9781845429485.

- ↑ Locke, J. (1692, January 2). A letter to Clarke. Retrieved 6 September 2004.

- ↑ Forté, B. (2000, June 15). The Statute of Queen Anne. Retrieved 1 September 2004.

- ↑ Shirata, H. (1992). The origin of two American copyright theories: A case of the reception of English law. Retrieved 6 September 2004.

- ↑ U.S. Constitutional Convention. (1787). Constitution of the United States. Retrieved 1 September 2004.

- ↑ Washington, G. (1790, July 17). The First U.S. Copyright Law. Columbian Centinel. Retrieved 21 August 2004.

- ↑ Jefferson, T. (1813, August 13). Thomas Jefferson letter to Isaac McPherson 13:333–34. Foundation Constitution, 16(25). Retrieved 21 August 2004.

- ↑ as cited in Vaidhyanathan, S. (2001). Copyrights and copywrongs: The rise of intellectual property and how it threatens creativity. New York: New York University Press. p.43.

- ↑ McGreal, R. (2004). Stealing the goose: Copyright and learning. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 5(3). Retrieved on 30 December 2010.

Who steals the goose from off the common

But leave the greater villain loose

Who steals the common from off the goose.

—Anonymous protest poem, 1764 or 1821

Orientation

Quiz

Indicate whether the following statements are true or false:

Copyright: A foreign concept to the ancient mind

Copyright in the common law countries (British legal heritage) began officially in the eighteenth century. Prior to that, ancient scribes (the earliest copiers) in writing the classics and sacred books of different religions were quite comfortable in excluding, substituting, amending, expanding, and abridging their materials. In the fourth century BC, Aristotle wrote:

The ancients had no proscriptions against copying or what we conceive today as plagiarism. Our ancestors’ understanding of the world was housed in stories – not dogma. Storytellers had no “moral” right to protect their tales. No one questioned the right of anyone to copy these and other works. “The concept of copyright was utterly foreign to the ancient mind”.[2]

Going to war for the right to copy a book

In Ireland in the sixth century there occurred the earliest known judgment on the right to copy. An Irish monk, Columcille, copied without permission St. Jerome’s psalter, a hymn book belonging to St. Finnian, the abbot of another monastery. Finnian asked Columcille to return the copy of the book claiming it to be stolen property and was refused. Finnian appealed to the High King of Ireland, King Diarmait, who pronounced the judgement in Finnian’s favour: “To every cow its calf to every book its copy.” Columcille responded to this adverse judgement with force and met the king’s men in battle at Cuildremne in 561. Columcille was triumphant and King Diarmait was exiled from Ireland, but as a result more than 3 000 men lay dead.[3] Columcille was later also exiled to Scotland, where he is known as St. Columba.[4] It could be said that although he lost the court case, with the battle, he won his point. This battle resolved the copyright issue in favour of openness for more than a millennium. The Irish monks continued copying books, spread out from Scotland, and brought the enlightenment to Europe.[5]

Many authors but only a few presses: An early distribution monopoly

The printing press, with its capacity to mass produce copies, came to Europe in the 15th century. There were few presses and many authors, so the printers gained control over the books that were produced, usually by paying authors a one-time fee. Monarchs found it easier to tax and control the few printers than tax all the authors, so they granted them monopolistic rights in return for taxes and censorship. The Stationers Company, which was made up of members of a printing guild, was granted a printing monopoly in 1557 in order to prevent the spread of Protestant writing in England.[6] During the Cromwellian period, the print monopolies were strengthened although the censorship was then directed against opponents of Puritanism.

It is during this period that copying without referencing the author became socially unacceptable. Ben Johnson was one of the first authors to use the term “plagiary” in English with its current meaning. The Oxford English Dictionary provides an earlier reference from Montagu in 1621, who used the word “plagiarisme” in the sense of purloining someone’s work.[7] Howard argues, therefore, that plagiarism is a historical construction rather than a moral category.[8] Downes acknowledges that plagiarism, while being mendacious, is not theft. Rather it is “a breach of trust between the plagiarizer and the reader . . . a misrepresentation of one’s self as something one is not.”[9]

Origins of copyright

Our modern concept of copyright in British common law has developed from the Statute of Queen Anne 1710 An Act for the Encouragement of Learning. It was passed for the purpose of promoting learning, specifically to encourage “learned men to compose and write useful books”.[10] Up until then, the publishers could pass on their royal grants of copyright to their heirs in perpetuity. This Act was a consequence of the 1707 Act of Union with Scotland to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain. Scottish booksellers would not accept the English monopoly of the London Stationers’ Company. This first copyright law had the purpose of breaking the Stationers’ monopoly and so, it was not a mechanism for protecting copyright controller’s rights as it is often portrayed nowadays. A number of features of the Act served the interests of the general public, for instance[11]:

Therefore, copyright law was expressly introduced to limit the rights of the previous monopoly of control.

In the Statute of Queen Anne, copyright was wrested from the printers and vested in the authors. This right was limited to a maximum of 28 years, after which works entered the public domain. So in effect, this statute created the public domain – the intellectual commons. This is the most important aspect of this law for the public and for education. It created a body of works that could be copied, altered, adapted, or tweaked by anyone for amusement, profit, or enlightenment. In addition, Article IX gave a special exemption to universities to ensure that none of their traditional copying rights were affected. This was no coincidence, intellectuals like John Locke actively campaigned for the repeal of the monopoly in the book trade and strongly condemned the restrictions on science caused by the monopolies of the Stationers Company.[12]

Forté explains: “Copyright isn’t on a par with the right to life, liberty, fraternity and equality before the law. It’s a privilege extended to us by our fellow citizens because they recognise the value they get out of our efforts.”[13] Copyright was never intended to be primarily a vehicle for protecting the rights of the copyright holders. On the contrary, copyright was initiated specifically to promote learning by removing the perpetual rights of the copyright controllers transferring the rights to the authors and imposing a reasonable time limit on their privilege.

Most of the colonies that formed the United States had laws that were based on the Statute of Queen Anne.[14] So it is not co-incidental that the U.S. Constitution echoes this purpose. It specifically refers to Congress’s duty in Article I Section 8:

This was followed by the Copyright Act 1790: An Act for the Encouragement of Learning and it was signed by George Washington.[16] Like the Statute of Queen Anne, this act (as the title suggests) was enacted specifically for the “encouragement of learning” and is meant to protect the rights of copyright holders only insofar as it serves that purpose. Thomas Jefferson expressly opposed linking copy rights to property rights, writing in 1813: “Inventions then cannot, in nature, be a subject of property.”[17] President Madison wrote: “…incentive, not property, or natural law is the foundational justification for American copyright.”[18]

Thus the origin of copyright suggests that there is no common law support for intellectual property. It is a privileged monopoly, not a right. Since these laws were first enacted, the copyright controllers have successfully waged a continuous war aiming to extend their rights at the expense of education and the general public, morphing the meaning of copyright in the public’s mind to become “intellectual property.”

Note that other countries have different traditions. For example most of continental Europe, Francophone Africa and Latin America follow the Napoleonic Code, which is based on “droit d’auteur” (author’s rights). Indigenous copyright too follows varied customs and traditions.

Closing reflection

In “Stealing the goose: Copyright and learning” (from which this page was adapted) Rory McGreal concludes:

Fortunately, in a digital world, Creative Commons provides the legal tools for education institutions to restore some of the balance by granting permissions and freedom to create new knowledge with fewer restrictions.

Do you agree with this position?

Share with us your thoughts about the development of copyright. Post your contribution on WENotes. Below are two questions to get you thinking. You might respond In my opinion…. .

You must be logged in to post to WEnotes.

Note: Your comment will be displayed in the course feed.

Further reading

Reading

We recommend the following sources for further reading:

Acknowledgements

This subsection was adapted from:

McGreal, R. (2004). Stealing the goose: Copyright and learning. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 5(3). Retrieved from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/205

Notes

Content is available under the

Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike License.

Privacy Policy | Authors