Value is the relative lightness or darkness of a shape in relation to another. The value scale, bounded on one end by pure white and on the other by black, and in between a series of progressively darker shades of grey, gives an artist the tools to make these transformations. The value scale below shows the standard variations in tones. Values near the lighter end of the spectrum are termed high-keyed, those on the darker end are low-keyed.

Oliver Harrison, Value scale

In two dimensions, the use of value gives a shape the illusion of mass and lends an entire composition a sense of light and shadow. The two examples below show the effect value has on changing a shape to a form.

-

Oliver Harrison, Two-dimensional shapes

-

Oliver Harrison, With value, the shapes take on the illusion of three-dimensional forms

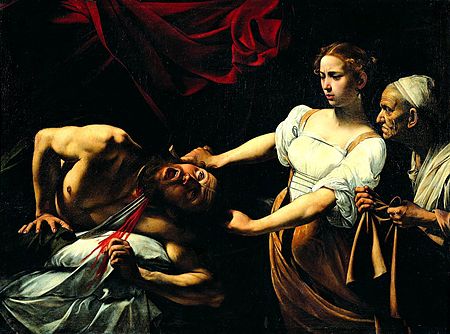

Caravaggio, Guiditta Decapitates Oloferne, 1598, oil on canvas. National Gallery of Italian Art, Rome

This same technique brings to life what begins as a simple line drawing of a young man’s head in Michelangelo’s Head of a Youth and a Right Hand from 1508. Shading is created with line (refer to our discussion of line earlier in this unit) or tones created with a pencil. Artists vary the tones by the amount of resistance they use between the pencil and the paper they’re drawing on. A drawing pencil’s leads vary in hardness, each one giving a different tone than another. Washes of ink or color create values determined by the amount of water the medium is dissolved into.

The use of high contrast, placing lighter areas of value against much darker ones, creates a dramatic effect, while low contrast gives more subtle results. These differences in effect are evident in Guiditta Decapitates Oloferne by the Italian painter Caravaggio, and Robert Adams’ photograph Untitled, Denver from 1970-74. Caravaggio uses a high contrast palette to an already dramatic scene to increase the visual tension for the viewer, while Adams deliberately makes use of low contrast to underscore the drabness of the landscape surrounding the figure on the bicycle.

Value

Value is the relative lightness or darkness of a shape in relation to another. The value scale, bounded on one end by pure white and on the other by black, and in between a series of progressively darker shades of grey, gives an artist the tools to make these transformations. The value scale below shows the standard variations in tones. Values near the lighter end of the spectrum are termed high-keyed, those on the darker end are low-keyed.

In two dimensions, the use of value gives a shape the illusion of mass and lends an entire composition a sense of light and shadow. The two examples below show the effect value has on changing a shape to a form.

Oliver Harrison, Two-dimensional shapes

Oliver Harrison, With value, the shapes take on the illusion of three-dimensional forms

This same technique brings to life what begins as a simple line drawing of a young man’s head in Michelangelo’s Head of a Youth and a Right Hand from 1508. Shading is created with line (refer to our discussion of line earlier in this unit) or tones created with a pencil. Artists vary the tones by the amount of resistance they use between the pencil and the paper they’re drawing on. A drawing pencil’s leads vary in hardness, each one giving a different tone than another. Washes of ink or color create values determined by the amount of water the medium is dissolved into.

The use of high contrast, placing lighter areas of value against much darker ones, creates a dramatic effect, while low contrast gives more subtle results. These differences in effect are evident in Guiditta Decapitates Oloferne by the Italian painter Caravaggio, and Robert Adams’ photograph Untitled, Denver from 1970-74. Caravaggio uses a high contrast palette to an already dramatic scene to increase the visual tension for the viewer, while Adams deliberately makes use of low contrast to underscore the drabness of the landscape surrounding the figure on the bicycle.

Content is available under the

Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike License.

Privacy Policy | Authors