As part of your induction process into critical reasoning, we would like to introduce you to Socrates, Plato and Descartes, three well-known and famous philosophers, and Thrasymachus, a relatively unknown thinker and exponent of the sophists, who became famous in Athens during the 5th century BC:

|

|

Socrates (pronounced: s.kr.ti.z) (c.469– 399 BC), is the most enigmatic figure in Greek philosophy, known only through the classical accounts of this students. Plato’s dialogues are the most comprehensive accounts of Socrates.

|

|

|

Plato (pronounced: ple.to.) (c. 428–347 BC), is the best known and most widely studied of all the ancient Greek philosophers. Along with his teacher, Socrates, and his student, Aristotle, Plato helped to lay the foundation of science and Western philosophy.

|

|

|

René Descartes (French pronunciation: [..ne deka.t], (1596– 1650), was a French philosopher. He has been dubbed the “Father of Modern Philosophy”, and much of subsequent Western philosophy is a response to his writings, which continue to be studied closely to this day. In particular, his Meditations continues to be a standard text at most university philosophy departments.

|

As you can see from their pictures, the gentlemen were born quite some time before you drew your first breath. However, their arguments form part of the classic history of the subject field Philosophy and as such you will see them in action below.

What is an Argument?

An argument is a group of statements. One of these statements is the conclusion of the argument. The other statements are the premises that are intended to convince the reader that the conclusion is true.

Tune into a local Talk Radio station and/or watch a debate in a current affairs or new broadcast on TV. Then think about the following questions:

- What, according to you, is an argument?

- What distinguishes a ‘good’ or ‘convincing’ argument from a ‘bad’ or ‘unconvincing’ argument?

Transcript 1

Now we will engage with the transcript of an argument on the topic of Affirmative Action as practised in South Africa. Before we begin:

- Write down your own opinion on the issue of affirmative action in your journal.

- Now read the following transcript. Whose argument do you find most convincing and why?

Edward: All human beings deserve equal treatment, regardless of gender or skin colour. It is a matter of fairness that all people of good will and rational thinking should be able to agree on. Isn’t that what South Africa’s Constitution is all about? Isn’t that what the feminist movement was originally all about? The underlying principle is to treat all people, regardless of gender or skin colour equally. To discriminate against anyone on the basis of gender or race, white males included, is inherently unfair and hence ethically unjustified.

Samantha: So, Edward, you are claiming that all discrimination on the basis of race and gender is inherently unfair. But have you considered the damage caused by past discrimination? No one can deny the South African history of racism and genderism. If the effects of that history were behind us, affirmative action would certainly be unnecessary. But the fact of the matter is that those effects of past discrimination are not behind us. Look around you and tell me who still have the capital and property rights in their hands. If we really believe in justice and equal opportunity, then we have to compensate for the effects of past discrimination on the basis of race and gender.

Edward: Certainly, Samantha, compensatory justice is a noble ideal. But there is a serious flaw in your argument. Compensatory justice for one group brings harm to another, and when the harmed group is not responsible for the plight of the other groups, you are punishing the innocent for the sins of their ancestors. To discriminate against a young white male or a person from a minority group on the basis of what happened before they were born is certainly not fair.

Samantha: I hear what you say, Edward. But I firmly believe that affirmative action is the only way to overcome current racism and genderism. Women remain subject to sexual harassment, and minority groups remain subject to stereotyping that continues to take its toll. You can hear it in casual conversations about women and minority groups and you can study the statistics to discover how bad it is.

Edward: Honestly Samantha, do you really believe that affirmative-action programmes will solve the core problem of discrimination, be it against blacks, whites, women or minority groups? Whatever the purpose of affirmative action, the result is racial tension and increased gender polarisation. A lot of white males and persons from minority groups justifiably feel cheated by affirmative action which denies them the jobs and promotions they are qualified for because they are white males or from a minority group. Affirmative action is thus not bringing us to a colour-blind and gender-blind society but to an increasingly polarised one.

Samantha: You know, Edward, I have never said that affirmative action programmes will eradicate discrimination. My point is that affirmative action is a way to provide compensation for injuries suffered in the past and a way to remove benefits that were undeservedly enjoyed by those who belonged to the dominant group.

Edward: Tell me, Samantha, do you justify preferential treatment programmes solely on the principle of compensation for past injuries?

Samantha: Yes indeed, I do. And I believe it is wrong to think that programmes geared to providing preferential treatment are objectionable, given past practices of discrimination based on racism and genderism.

Edward: But how can you claim this? In my opinion, preferential treatment is nothing but reverse discrimination, founded on racism and genderism. Your argument is intellectually inconsistent in the sense that you now support preferential treatment while you opposed it in the past. Reverse discrimination thus undermines equality because it violates the very idea of equal justice under law for all citizens. What is more, reverse discrimination is prohibited by our Constitution and ethical commitment to equal justice for all.

The following two extracts are examples of arguments in the philosophical sense. The first is from Descartes’s Meditations:

For, since I am accustomed to the distinction of existence and essence in all other objects, I am readily convinced that existence can be disjoined even from the divine essence, and that thus God can be conceived as non-existent. But on more careful consideration it becomes obvious that existence can no more be taken away from the divine essence than the magnitude of its three angles together (that is, their being equal to two right angles) can be taken away from the essence of a triangle; or than the idea of a valley can be taken away from the idea of a hill. So it is not less absurd to think of God (that is, a supremely perfect being) lacking existence (that is, lacking a certain perfection) than to think of a hill without a valley.

The second transcript below is a discussion, recorded in Plato’s Republic, between Socrates and Thrasymachus, on what is just and right:

Transcript 2

Thrasymachus:… I say that “right” is the same thing in all states, namely the interest of the established ruling class; and this ruling class is the “strongest” element in each state, and so if we argue correctly we see that “right” is always the same, the interest of the stronger party.

Socrates:… You say that obedience to the ruling power is right and just?

Thrasymachus: I do.

Socrates: And are those in power in the various states infallible or not?

Thrasymachus: They are, of course, liable to make mistakes.

Socrates: When they proceed to make laws, then, they may do the job well or badly.

Thrasymachus: I suppose so.

Socrates: And if they do it well the laws will be in their interest, and if they do it badly they won’t, I take it.

Thrasymachus: I agree.

Socrates: But their subjects must obey the laws they make, for to do so is right.

Thrasymachus: Of course.

Socrates: Then, according to your argument, it is right not only to do what is in the interest of the stronger party but also the opposite.

Thrasymachus: What do you mean?

Socrates: My meaning is the same as yours, I think. Let us look at it more closely. Did we not agree that when the ruling powers order their subjects to do something they are sometimes mistaken about their own best interest, and yet it is right for the subject to do what his ruler enjoins?

Thrasymachus: I suppose we did.

Socrates: Then you must admit that it is right to do things that are not in the interest of the rulers, who are the stronger party; that is, when the rulers mistakenly give orders that will harm them and yet (so you say) it is right for their subjects to obey those orders. For surely, my dear Thrasymachus, in those circumstances it follows that it is right to do the opposite of what you say is right, in that the weaker are ordered to do what is against the interest of the stronger.

The first transcript is an example of the meaning of the term “argument” according to sense (2) above. In other words, “argument” used in this sense means a group of statements intended to establish the truth of a claim. The second extract is an example of the meaning of “argument” according to sense (3) above. That is, “argument” used in this sense means an exchange or debate between two or more people who disagree with each other, in which each person gives reasons to support his or her position.

We will concern ourselves mostly with arguments in the sense of (2) in the sections which follow.

Here is a definition of an argument:

An argument is a group of statements. One of these statements is the conclusion of the argument. The other statements are the premises that are intended to convince the reader that the conclusion is true.

Before we can identify premises and conclusions in arguments, we need to know what is meant by “premise” and “conclusion”.

Premises are those statements in an argument that have the function of supporting the conclusion. Premises therefore provide reasons for accepting the conclusion of an argument, although not all reasons are good reasons or relevant reasons.

Conclusions are those statements in an argument which the premises are intended to support. The purpose of an argument is to establish the truth or acceptability of the conclusion. A sound argument is one in which the conclusion is shown to be true or acceptable because it follows from the truth or acceptability of the premises and the valid structure of the argument.

Let us look at the following argument to explain what premises and conclusions are:

My nose itched this morning. So I am going to be upset later today.

In this argument the first statement is a premise and the second statement is a conclusion. It is obvious that the conclusion is not supported by the premise. There is no relation between my being upset later today and the fact that my nose itched this morning. When we analyze arguments it is important to identify premises and conclusions clearly.

| Indicators of premises

|

Indicators of conclusions

|

- because

- for

- if …

- moreover

- since

- for the reason that

- given that

- whereas

- insofar as

- firstly, secondly, thirdly, etc

- seeing that

- in the light of

|

- therefore

- in conclusion

- so

- it follows that

- we can conclude that

- consequently

- this shows that

- accordingly

- subsequently

- as a consequence

- thus

- hence

- then …

|

In the online references you will find a detailed discussion on how to identify premises and conclusions in arguments.

The Structure of Arguments

A full analysis of an argument not only identifies which statements are premises and which are conclusions, but also identifies the structure of the argument. The structure shows how the conclusion of an argument is related to its premises. Note that premises and conclusions are related to each other in different ways in various arguments. Sometimes a premise supports the conclusion independently; at other times the premises support the conclusion interdependently. You will find more information about the structure of arguments in the online references. Here we will only explain briefly the two different ways premises and conclusions are related to each other, by giving you two examples.

The following is an example of a simple argument, where the premises support the conclusion independently:

Abortion preserves the mother’s rights over her own body. It also prevents the birth of unwanted children. Therefore, abortion should be made legally available.

Let us bracket and number the statements of the above argument:

[Abortion preserves the mother’s rights over her own body]. 1

[It also prevents the birth of unwanted children]. 2

Therefore, [abortion should be made legally available]. 3

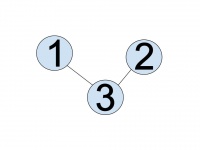

Statement 1 supports the conclusion independently of statement 2 (assuming it is true or acceptable) and statement 2 supports the conclusion independently of statement 1 (assuming it is true or acceptable). We can represent the structure of this argument in the following way:

Now, let us take an example of a simple argument in which the premises support the conclusion interdependently.

All human beings are mortal. Sue is a human being. Therefore, Sue is mortal.

Let us bracket and number the statements of the above argument:

[All human beings are mortal.] 1

[Sue is a human being.] 2

Therefore, [Sue is mortal]. 3

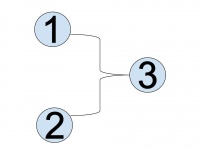

Statement 1 and statement 2 support the conclusion interdependently. Statements 1 and 2 together conclusively support the conclusion (assuming that both premises are true or acceptable). We can represent the structure of this argument in the following way:

Note: Not all arguments are complete. Sometimes an argument has a missing premise. A full analysis of an argument requires us to fill in the missing premise. A premise is missing in an argument if, without it, the premises do not provide sufficient support for the conclusion, given that the premises are true. For example:

John is a poor student because he spends his time reading comic books and magazines.

This argument requires the further premise:

Students who spend their time reading comic books and magazines are poor students

in order for the premises to provide sufficient support for the conclusion, given that the premises are true. Fully stated, the argument is as follows:

Students who spend their time reading comic books and magazines are poor students. John spends his time reading comic books and magazines. Therefore, John is a poor student.

Remember that if we accept the premises of an argument, and also accept the validity of the structure of the argument, then we are logically compelled to accept the conclusion. Conversely, if we do not accept the conclusion of an argument, then we are logically compelled to deny the truth or acceptability of at least one of the premises, or we are logically compelled to deny the validity of the structure of the argument. Sometimes you will want to say that both the premises and the structure of the argument are unacceptable.

Finally, an argument may imply its conclusion, rather than fully state it. In these cases we have to supply the implied conclusion in the same way that we have to supply the missing premises in an argument which is not fully stated.

Consider the following passages and then bracket and number the statements, underline the signal words (if there are any) and analyze the following arguments:

- Censorship of literature and film cannot easily be enforced. Moreover, the criteria for censorship are either arbitrary or partisan.

- Without a good supply of rain food production and industry will suffer. Our future depends on strong agricultural and industrial growth. Therefore, we should do whatever we can to promote good water management.

- The objections to the new dam construction are short-sighted. Firstly, more people will benefit from a new dam than those people who will suffer because of losing their homes and farms. Secondly, those who do lose their homes and farms will be compensated and, thirdly, many jobs will be created by the construction of a new dam in the area.

- Most workers want better pay and better work conditions. It follows from this that most workers are in favour of trade unions.

Feedback: We will help you to complete examples (1) and (2). Apply the knowledge and skills you have gained from the previous discussions and activities and complete examples (3) and (4) on your own.

Censorship of literature and film cannot easily be enforced. Moreover, the criteria for censorship are either arbitrary or partisan.

Let us bracket and number the statements, underline the signal words and analyze the argument:

[1] Censorship of literature and film cannot easily be enforced. Moreover, the criteria for censorship are either arbitrary or partisan.

Let us bracket and number the statements, underline the signal words and analyze the argument:

[Censorship of literature and film cannot easily be enforced.] 1

Moreover, [the criteria for censorship are either arbitrary or partisan]. 2

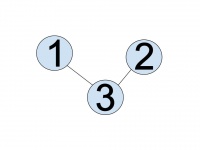

The argument contains a missing conclusion. The implied conclusion is that censorship is unacceptable. The structure of the argument can then be represented as follows:

[2] Without a good supply of rain food production and industry will suffer. Our future depends on strong agricultural and industrial growth. Therefore, we should do whatever we can to promote good water management.

We have to bracket and number the statements, underline the signal words and analyze the argument:

[Without a good supply of rain food production and industry will suffer.] 1

[Our future depends on strong agricultural and industrial growth.] 2

Therefore, [we should do whatever we can to promote good water management]. 3

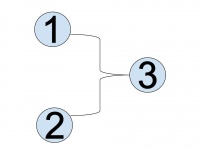

The structure of the argument can be represented as follows:

The diagrams show that premises 1 and 2 support the conclusion interdependently. Neither premise 1 nor premise 2 on its own provides sufficient ground to accept the conclusion. Both premises need to be true for they support the conclusion together. If you are still unsure about how premises and conclusions are related to each other in arguments, you could reread the relevant sections in the online references supplied.

In this section we have explored the idea that an argument has a structure. The way in which we evaluate an argument depends, partially, on its structure. Through practice and experience you will become aware of the structure of arguments and you will therefore find it unnecessary to portray arguments in diagrammatic form.

Applying your knowledge and skills to analyzing arguments

You will hardly believe it, but if you have actively participated in your initiation process of becoming a critical thinker, you will now be at the stage where you have the competence to analyze arguments.

Here is a summary of the steps in argument analysis:

- Step one — Clarify the meaning of the argument.

- Step two — Bracket and number the statements and underline the signal words.

- Step three — Identify the conclusion(s) of the argument.

- Step four — Identify the premises of the argument.

- Step five — Provide a representation of the structure of the argument.

Empirical vs. Value Arguments

The difference between empirical and value arguments is easy to detect if we understand that empirical arguments are about facts, whereas value arguments are about values. Let us now attempt to formulate the difference between these two types of arguments in greater detail.

An empirical argument asserts that some empirically determinable facts hold. For example, when I say that there is a power failure in town, my claim is either correct or it is not. What makes it correct is some factual state of affairs in the world. The truth or correctness of my claim does not depend on what I feel, believe or value.

A value argument asserts a claim of preference or a moral judgement about right and wrong, good and bad. For example, when I claim that the use of animals in biomedical research is morally wrong, there are no independent facts against which the correctness of my claim can be determined. The correctness or otherwise of my claim depends on argumentation and on substantiated reasons offered in support of my claim.

Summary

In this topic we have learned what an argument is; what premises and conclusions are; how to identify premises and conclusions in arguments; how to use techniques for analyzing arguments; and how to distinguish between empirical and value arguments. The basic competence that you have gained in analyzing arguments will also serve you well when we evaluate arguments. This is the focus of our next topic.

As part of your induction process into critical reasoning, we would like to introduce you to Socrates, Plato and Descartes, three well-known and famous philosophers, and Thrasymachus, a relatively unknown thinker and exponent of the sophists, who became famous in Athens during the 5th century BC:

As you can see from their pictures, the gentlemen were born quite some time before you drew your first breath. However, their arguments form part of the classic history of the subject field Philosophy and as such you will see them in action below.

What is an Argument?

An argument is a group of statements. One of these statements is the conclusion of the argument. The other statements are the premises that are intended to convince the reader that the conclusion is true.

Tune into a local Talk Radio station and/or watch a debate in a current affairs or new broadcast on TV. Then think about the following questions:

Transcript 1

Now we will engage with the transcript of an argument on the topic of Affirmative Action as practised in South Africa. Before we begin:

Edward: All human beings deserve equal treatment, regardless of gender or skin colour. It is a matter of fairness that all people of good will and rational thinking should be able to agree on. Isn’t that what South Africa’s Constitution is all about? Isn’t that what the feminist movement was originally all about? The underlying principle is to treat all people, regardless of gender or skin colour equally. To discriminate against anyone on the basis of gender or race, white males included, is inherently unfair and hence ethically unjustified.

Samantha: So, Edward, you are claiming that all discrimination on the basis of race and gender is inherently unfair. But have you considered the damage caused by past discrimination? No one can deny the South African history of racism and genderism. If the effects of that history were behind us, affirmative action would certainly be unnecessary. But the fact of the matter is that those effects of past discrimination are not behind us. Look around you and tell me who still have the capital and property rights in their hands. If we really believe in justice and equal opportunity, then we have to compensate for the effects of past discrimination on the basis of race and gender.

Edward: Certainly, Samantha, compensatory justice is a noble ideal. But there is a serious flaw in your argument. Compensatory justice for one group brings harm to another, and when the harmed group is not responsible for the plight of the other groups, you are punishing the innocent for the sins of their ancestors. To discriminate against a young white male or a person from a minority group on the basis of what happened before they were born is certainly not fair.

Samantha: I hear what you say, Edward. But I firmly believe that affirmative action is the only way to overcome current racism and genderism. Women remain subject to sexual harassment, and minority groups remain subject to stereotyping that continues to take its toll. You can hear it in casual conversations about women and minority groups and you can study the statistics to discover how bad it is.

Edward: Honestly Samantha, do you really believe that affirmative-action programmes will solve the core problem of discrimination, be it against blacks, whites, women or minority groups? Whatever the purpose of affirmative action, the result is racial tension and increased gender polarisation. A lot of white males and persons from minority groups justifiably feel cheated by affirmative action which denies them the jobs and promotions they are qualified for because they are white males or from a minority group. Affirmative action is thus not bringing us to a colour-blind and gender-blind society but to an increasingly polarised one.

Samantha: You know, Edward, I have never said that affirmative action programmes will eradicate discrimination. My point is that affirmative action is a way to provide compensation for injuries suffered in the past and a way to remove benefits that were undeservedly enjoyed by those who belonged to the dominant group.

Edward: Tell me, Samantha, do you justify preferential treatment programmes solely on the principle of compensation for past injuries?

Samantha: Yes indeed, I do. And I believe it is wrong to think that programmes geared to providing preferential treatment are objectionable, given past practices of discrimination based on racism and genderism.

Edward: But how can you claim this? In my opinion, preferential treatment is nothing but reverse discrimination, founded on racism and genderism. Your argument is intellectually inconsistent in the sense that you now support preferential treatment while you opposed it in the past. Reverse discrimination thus undermines equality because it violates the very idea of equal justice under law for all citizens. What is more, reverse discrimination is prohibited by our Constitution and ethical commitment to equal justice for all.

The following two extracts are examples of arguments in the philosophical sense. The first is from Descartes’s Meditations:

The second transcript below is a discussion, recorded in Plato’s Republic, between Socrates and Thrasymachus, on what is just and right:

Transcript 2

Thrasymachus:… I say that “right” is the same thing in all states, namely the interest of the established ruling class; and this ruling class is the “strongest” element in each state, and so if we argue correctly we see that “right” is always the same, the interest of the stronger party.

Socrates:… You say that obedience to the ruling power is right and just?

Thrasymachus: I do.

Socrates: And are those in power in the various states infallible or not?

Thrasymachus: They are, of course, liable to make mistakes.

Socrates: When they proceed to make laws, then, they may do the job well or badly.

Thrasymachus: I suppose so.

Socrates: And if they do it well the laws will be in their interest, and if they do it badly they won’t, I take it.

Thrasymachus: I agree.

Socrates: But their subjects must obey the laws they make, for to do so is right.

Thrasymachus: Of course.

Socrates: Then, according to your argument, it is right not only to do what is in the interest of the stronger party but also the opposite.

Thrasymachus: What do you mean?

Socrates: My meaning is the same as yours, I think. Let us look at it more closely. Did we not agree that when the ruling powers order their subjects to do something they are sometimes mistaken about their own best interest, and yet it is right for the subject to do what his ruler enjoins?

Thrasymachus: I suppose we did.

Socrates: Then you must admit that it is right to do things that are not in the interest of the rulers, who are the stronger party; that is, when the rulers mistakenly give orders that will harm them and yet (so you say) it is right for their subjects to obey those orders. For surely, my dear Thrasymachus, in those circumstances it follows that it is right to do the opposite of what you say is right, in that the weaker are ordered to do what is against the interest of the stronger.

The first transcript is an example of the meaning of the term “argument” according to sense (2) above. In other words, “argument” used in this sense means a group of statements intended to establish the truth of a claim. The second extract is an example of the meaning of “argument” according to sense (3) above. That is, “argument” used in this sense means an exchange or debate between two or more people who disagree with each other, in which each person gives reasons to support his or her position.

We will concern ourselves mostly with arguments in the sense of (2) in the sections which follow.

Here is a definition of an argument:

Before we can identify premises and conclusions in arguments, we need to know what is meant by “premise” and “conclusion”.

Premises are those statements in an argument that have the function of supporting the conclusion. Premises therefore provide reasons for accepting the conclusion of an argument, although not all reasons are good reasons or relevant reasons.

Conclusions are those statements in an argument which the premises are intended to support. The purpose of an argument is to establish the truth or acceptability of the conclusion. A sound argument is one in which the conclusion is shown to be true or acceptable because it follows from the truth or acceptability of the premises and the valid structure of the argument.

Let us look at the following argument to explain what premises and conclusions are:

In this argument the first statement is a premise and the second statement is a conclusion. It is obvious that the conclusion is not supported by the premise. There is no relation between my being upset later today and the fact that my nose itched this morning. When we analyze arguments it is important to identify premises and conclusions clearly.

In the online references you will find a detailed discussion on how to identify premises and conclusions in arguments.

The Structure of Arguments

A full analysis of an argument not only identifies which statements are premises and which are conclusions, but also identifies the structure of the argument. The structure shows how the conclusion of an argument is related to its premises. Note that premises and conclusions are related to each other in different ways in various arguments. Sometimes a premise supports the conclusion independently; at other times the premises support the conclusion interdependently. You will find more information about the structure of arguments in the online references. Here we will only explain briefly the two different ways premises and conclusions are related to each other, by giving you two examples.

The following is an example of a simple argument, where the premises support the conclusion independently:

Let us bracket and number the statements of the above argument:

Statement 1 supports the conclusion independently of statement 2 (assuming it is true or acceptable) and statement 2 supports the conclusion independently of statement 1 (assuming it is true or acceptable). We can represent the structure of this argument in the following way:

Now, let us take an example of a simple argument in which the premises support the conclusion interdependently.

Let us bracket and number the statements of the above argument:

Statement 1 and statement 2 support the conclusion interdependently. Statements 1 and 2 together conclusively support the conclusion (assuming that both premises are true or acceptable). We can represent the structure of this argument in the following way:

Note: Not all arguments are complete. Sometimes an argument has a missing premise. A full analysis of an argument requires us to fill in the missing premise. A premise is missing in an argument if, without it, the premises do not provide sufficient support for the conclusion, given that the premises are true. For example:

This argument requires the further premise:

in order for the premises to provide sufficient support for the conclusion, given that the premises are true. Fully stated, the argument is as follows:

Remember that if we accept the premises of an argument, and also accept the validity of the structure of the argument, then we are logically compelled to accept the conclusion. Conversely, if we do not accept the conclusion of an argument, then we are logically compelled to deny the truth or acceptability of at least one of the premises, or we are logically compelled to deny the validity of the structure of the argument. Sometimes you will want to say that both the premises and the structure of the argument are unacceptable.

Finally, an argument may imply its conclusion, rather than fully state it. In these cases we have to supply the implied conclusion in the same way that we have to supply the missing premises in an argument which is not fully stated.

Consider the following passages and then bracket and number the statements, underline the signal words (if there are any) and analyze the following arguments:

Feedback: We will help you to complete examples (1) and (2). Apply the knowledge and skills you have gained from the previous discussions and activities and complete examples (3) and (4) on your own.

Let us bracket and number the statements, underline the signal words and analyze the argument:

Let us bracket and number the statements, underline the signal words and analyze the argument:

The argument contains a missing conclusion. The implied conclusion is that censorship is unacceptable. The structure of the argument can then be represented as follows:

We have to bracket and number the statements, underline the signal words and analyze the argument:

The structure of the argument can be represented as follows:

The diagrams show that premises 1 and 2 support the conclusion interdependently. Neither premise 1 nor premise 2 on its own provides sufficient ground to accept the conclusion. Both premises need to be true for they support the conclusion together. If you are still unsure about how premises and conclusions are related to each other in arguments, you could reread the relevant sections in the online references supplied.

In this section we have explored the idea that an argument has a structure. The way in which we evaluate an argument depends, partially, on its structure. Through practice and experience you will become aware of the structure of arguments and you will therefore find it unnecessary to portray arguments in diagrammatic form.

Applying your knowledge and skills to analyzing arguments

You will hardly believe it, but if you have actively participated in your initiation process of becoming a critical thinker, you will now be at the stage where you have the competence to analyze arguments.

Here is a summary of the steps in argument analysis:

Empirical vs. Value Arguments

The difference between empirical and value arguments is easy to detect if we understand that empirical arguments are about facts, whereas value arguments are about values. Let us now attempt to formulate the difference between these two types of arguments in greater detail.

An empirical argument asserts that some empirically determinable facts hold. For example, when I say that there is a power failure in town, my claim is either correct or it is not. What makes it correct is some factual state of affairs in the world. The truth or correctness of my claim does not depend on what I feel, believe or value.

A value argument asserts a claim of preference or a moral judgement about right and wrong, good and bad. For example, when I claim that the use of animals in biomedical research is morally wrong, there are no independent facts against which the correctness of my claim can be determined. The correctness or otherwise of my claim depends on argumentation and on substantiated reasons offered in support of my claim.

Summary

In this topic we have learned what an argument is; what premises and conclusions are; how to identify premises and conclusions in arguments; how to use techniques for analyzing arguments; and how to distinguish between empirical and value arguments. The basic competence that you have gained in analyzing arguments will also serve you well when we evaluate arguments. This is the focus of our next topic.

Content is available under the

Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike License.

Privacy Policy | Authors