Reserves and missions were both places of enforced cultural change and places to subversively maintain Indigenous identity.

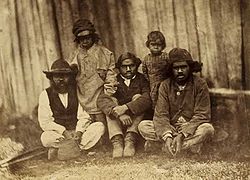

This photo was taken in Ngiyeempaa country and permission for its use has been given by Aunty Beryl Philp Carmichael, Ngiyeempaa Elder.

Reserves and Missions have been established and abandoned for the duration of Australia’s colonised history. The drive to ‘protect’ Indigenous people around the turn of the twentieth century supported the establishment of more Government reserves, homes and other institutions. Conditions were often harsh, sometimes abusive. Enforced by legislation, Indigenous lives were subject to poor living conditions and extreme bureaucratic control.

During the 1930s Depression, the aims of the Protection policy in New South Wales changed “as the government capitulated to the demands of rural whites for segregation” (McGrath, 1995, p. 59). Movement onto reserves was at its height in the 1930s when “whole communities” of Indigenous people were “moved hundreds of miles by cattle truck and dumped on the Protection Board Stations at Menindee, Brewarrina, Toomela and Burnt Bridge” (McGrath, 1995, p. 36).

At the same time, Aboriginal people in New South Wales were refused unemployment benefits during the Depression years under a policy that they must prove they had “performed a white man’s work” when applying for unemployment benefits, a clause which was used to exclude Indigenous people from payments (McGrath, 1995, p. 36). Yet in Victoria Indigenous people continued to receive unemployment benefits. This example displays one of the ways that Indigenous people were treated differently in different government jurisdictions.

While missions and reserves were often sites of control and attempted assimilation, they were also places of survival and resistance, and many have become important places for Indigenous communities today (Lydon, 2010).

You can look at maps showing the location of missions across Australia:

You can learn more about the Missions and Reserves in Victoria, at the ABC site ‘Mission Voices’ which includes historical text and oral histories:

This includes, for example, Cummeragunja, which was actually in NSW, right on the banks of the Murray, where the first mission ‘walk off’ took place in 1939:

Or Coranderrk, near Melbourne, the site of many protests:

You can learn more about NSW missions and reserves on the AIATSIS website:

You can learn more about Queensland missions and reserves on the AIATSIS website:

Here is an extract to consider:

Aboriginal Farmers at Parker’s Protectorate, Mt Franklin, Victoria in 1858. Aboriginal people who lost control of their lands were generally pushed into reserves or missions.

“Everything that related to a concentration camp was there [in Cherbourg reserve in Queensland]. You could not move without getting a permit. … We had to get a permit to go down and fish [at the river]. We had to get a permit to go to Murgon, which was four miles away – six kilometres – and it had a time set on it. If you came back five to ten minutes after that time expired, you would be put in jail for, maybe, a weekend. And they brought the curfew in. All lights had to be out at nine o’clock. If you were found out after dark or after the lights had gone out, you were put in jail. They even put searchlights on the vehicles – the police, the superintendent – and chased black fellas everywhere, hither and thither, throughout the night hours. … [T]hey took away our corroborees, they took away our culture. Our ancestors were not allowed to teach us our language; most of us know nothing of our language.” (Mr Peter Bird, cited in Commonwealth of Australia (2006). Unfinished business: Indigenous stolen wages”. ‘Retrieved, 3 July 2013

- Think about your day today. Under Protection legislation, could you have done everything you have done?

Key Idea

Reserves and missions were both places of enforced cultural change and places to subversively maintain Indigenous identity.

Reserves and Missions have been established and abandoned for the duration of Australia’s colonised history. The drive to ‘protect’ Indigenous people around the turn of the twentieth century supported the establishment of more Government reserves, homes and other institutions. Conditions were often harsh, sometimes abusive. Enforced by legislation, Indigenous lives were subject to poor living conditions and extreme bureaucratic control.

During the 1930s Depression, the aims of the Protection policy in New South Wales changed “as the government capitulated to the demands of rural whites for segregation” (McGrath, 1995, p. 59). Movement onto reserves was at its height in the 1930s when “whole communities” of Indigenous people were “moved hundreds of miles by cattle truck and dumped on the Protection Board Stations at Menindee, Brewarrina, Toomela and Burnt Bridge” (McGrath, 1995, p. 36).

At the same time, Aboriginal people in New South Wales were refused unemployment benefits during the Depression years under a policy that they must prove they had “performed a white man’s work” when applying for unemployment benefits, a clause which was used to exclude Indigenous people from payments (McGrath, 1995, p. 36). Yet in Victoria Indigenous people continued to receive unemployment benefits. This example displays one of the ways that Indigenous people were treated differently in different government jurisdictions.

While missions and reserves were often sites of control and attempted assimilation, they were also places of survival and resistance, and many have become important places for Indigenous communities today (Lydon, 2010).

You can look at maps showing the location of missions across Australia:

You can learn more about the Missions and Reserves in Victoria, at the ABC site ‘Mission Voices’ which includes historical text and oral histories:

This includes, for example, Cummeragunja, which was actually in NSW, right on the banks of the Murray, where the first mission ‘walk off’ took place in 1939:

Or Coranderrk, near Melbourne, the site of many protests:

You can learn more about NSW missions and reserves on the AIATSIS website:

You can learn more about Queensland missions and reserves on the AIATSIS website:

Required Reading

Pioneers of Love (2005). ‘The Native Problem’.

Reflection

Here is an extract to consider:

“Everything that related to a concentration camp was there [in Cherbourg reserve in Queensland]. You could not move without getting a permit. … We had to get a permit to go down and fish [at the river]. We had to get a permit to go to Murgon, which was four miles away – six kilometres – and it had a time set on it. If you came back five to ten minutes after that time expired, you would be put in jail for, maybe, a weekend. And they brought the curfew in. All lights had to be out at nine o’clock. If you were found out after dark or after the lights had gone out, you were put in jail. They even put searchlights on the vehicles – the police, the superintendent – and chased black fellas everywhere, hither and thither, throughout the night hours. … [T]hey took away our corroborees, they took away our culture. Our ancestors were not allowed to teach us our language; most of us know nothing of our language.” (Mr Peter Bird, cited in Commonwealth of Australia (2006). Unfinished business: Indigenous stolen wages”. ‘Retrieved, 3 July 2013

Content is available under the

Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike License.

Privacy Policy | Authors