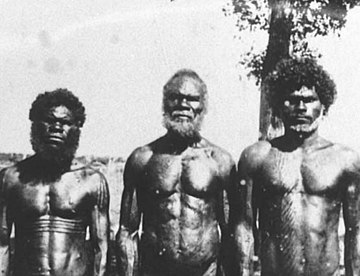

Men from Bathurst Island, 1939

Indigenous people were not immune to many European diseases and up to half the Indigenous population died as a result of these new diseases.

The common, contagious illnesses we are familiar with today, all arose from Europeans living in extremely close proximity to animals. Smallpox is originally from rodents. The various influenzas (the ‘flu) are shared with pigs (swine flu) and birds (bird flu). Measles diverged from a virus in cattle. Over many thousands of years, Europeans had shared these diseases with their animals and those humans who did not die developed immunities. The Indigenous people of Australia had no immunity and introduced diseases such as smallpox and measles killed half, if not more, of the original population. Diseases that have impacted on Indigenous people include measles, chickenpox, whooping cough, mumps, scarlet fever, diphtheria, tuberculosis, influenza, pneumonia, typhoid fever, venereal disease and leprosy. In many cases, the diseases spread faster than the British (Campbell, 2002).

Introduced diseases had devastating effects on many Aboriginal groups before they came into contact with Europeans. Some populations were halved or virtually wiped out. The severity of disease caused both personal suffering and crises in community organisation and leadership. This meant some groups were already in a weakened position when Europeans arrived in their territory. As communities were displaced they suffered from starvation or severely depleted diets. From the later in the nineteenth century, government policies meant Aboriginal people were denied the medical care that was becoming increasingly available to the settler population (McCallman et. al, 2001).

The colonies differed considerably. People in the south-eastern areas of Australia were badly affected by smallpox, whilst northerners seem to have had greater immunity because to this disease, possibly because they had already encountered it via earlier Macassan visitors.

Key Idea

Indigenous people were not immune to many European diseases and up to half the Indigenous population died as a result of these new diseases.

The common, contagious illnesses we are familiar with today, all arose from Europeans living in extremely close proximity to animals. Smallpox is originally from rodents. The various influenzas (the ‘flu) are shared with pigs (swine flu) and birds (bird flu). Measles diverged from a virus in cattle. Over many thousands of years, Europeans had shared these diseases with their animals and those humans who did not die developed immunities. The Indigenous people of Australia had no immunity and introduced diseases such as smallpox and measles killed half, if not more, of the original population. Diseases that have impacted on Indigenous people include measles, chickenpox, whooping cough, mumps, scarlet fever, diphtheria, tuberculosis, influenza, pneumonia, typhoid fever, venereal disease and leprosy. In many cases, the diseases spread faster than the British (Campbell, 2002).

Introduced diseases had devastating effects on many Aboriginal groups before they came into contact with Europeans. Some populations were halved or virtually wiped out. The severity of disease caused both personal suffering and crises in community organisation and leadership. This meant some groups were already in a weakened position when Europeans arrived in their territory. As communities were displaced they suffered from starvation or severely depleted diets. From the later in the nineteenth century, government policies meant Aboriginal people were denied the medical care that was becoming increasingly available to the settler population (McCallman et. al, 2001).

The colonies differed considerably. People in the south-eastern areas of Australia were badly affected by smallpox, whilst northerners seem to have had greater immunity because to this disease, possibly because they had already encountered it via earlier Macassan visitors.

Content is available under the

Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike License.

Privacy Policy | Authors