History is not a series of agreed ‘facts’ but is open to interpretation and argument, and the telling of history itself changes over time as we ask new questions about the past.

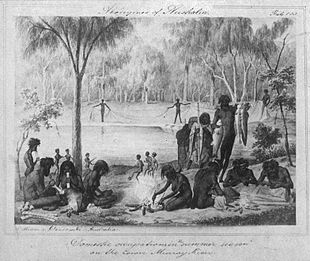

1857 depiction of the Jarijari (Nyeri Nyeri) people near Merbein engaged in recreational activities, including a type of Aboriginal football.[123][124]

For much of the period of non-Indigenous settlement in this country, Australia’s history has been told as triumph over difficult odds, a wild country tamed by intrepid explorers and the hard work of settlers, a civilisation built in a wilderness, a Commonwealth established peacefully and rationally.

Before the advent of Aboriginal history as a distinct discipline in the 1970s, twentieth century histories of Australia wrote Aboriginal people out of the national story, considering Indigenous Australians to be of marginal importance to the colonisation of the country. The attitude of historians was summed up in a school text of 1917, which expressed the conviction that there was a “good reason” why the “dark-skinned wandering tribes” should not be included in histories of Australia, as “they have nothing that can be called a history… Change and progress are the stuff of which history is made: these blacks knew no change and no progress, as far as we can tell”. While the anthropologist might study Aboriginal peoples, the historian had different priorities, with it being “his business to tell how these white folk found the land, how they settled in it, how they explored it, and how they gradually made it the Australia we know today” (Murdoch, 1917, quoted in Attwood, 2005, p. 16).

From the 1970s non-Indigenous and Indigenous historians began to question this story; they were influenced by Indigenous politics and activism and began to talk to Indigenous people about their version of history, to see Australian history as having different sides.

In the past 20 years, however, Australia’s history as it pertains to Indigenous people has been highly contested, in what is commonly called the History Wars. Some non-Indigenous historians, and some politicians, have felt that Australian history is now too bleak, and not triumphant enough (Macintyre & Clark, 2003). Much of this debate has focussed on the extent of violence which occurred on the ‘frontier’, as white colonist progressively took over more and more land across the continent, and in particular the question of massacres. Settler Australians often find it difficult to accept that violent dispossession was part of the foundation of the nation.

From an Indigenous perspective, Australia’s history is one of invasion, war, displacement and social destruction.

Key Idea

History is not a series of agreed ‘facts’ but is open to interpretation and argument, and the telling of history itself changes over time as we ask new questions about the past.

For much of the period of non-Indigenous settlement in this country, Australia’s history has been told as triumph over difficult odds, a wild country tamed by intrepid explorers and the hard work of settlers, a civilisation built in a wilderness, a Commonwealth established peacefully and rationally.

Before the advent of Aboriginal history as a distinct discipline in the 1970s, twentieth century histories of Australia wrote Aboriginal people out of the national story, considering Indigenous Australians to be of marginal importance to the colonisation of the country. The attitude of historians was summed up in a school text of 1917, which expressed the conviction that there was a “good reason” why the “dark-skinned wandering tribes” should not be included in histories of Australia, as “they have nothing that can be called a history… Change and progress are the stuff of which history is made: these blacks knew no change and no progress, as far as we can tell”. While the anthropologist might study Aboriginal peoples, the historian had different priorities, with it being “his business to tell how these white folk found the land, how they settled in it, how they explored it, and how they gradually made it the Australia we know today” (Murdoch, 1917, quoted in Attwood, 2005, p. 16).

From the 1970s non-Indigenous and Indigenous historians began to question this story; they were influenced by Indigenous politics and activism and began to talk to Indigenous people about their version of history, to see Australian history as having different sides.

In the past 20 years, however, Australia’s history as it pertains to Indigenous people has been highly contested, in what is commonly called the History Wars. Some non-Indigenous historians, and some politicians, have felt that Australian history is now too bleak, and not triumphant enough (Macintyre & Clark, 2003). Much of this debate has focussed on the extent of violence which occurred on the ‘frontier’, as white colonist progressively took over more and more land across the continent, and in particular the question of massacres. Settler Australians often find it difficult to accept that violent dispossession was part of the foundation of the nation.

From an Indigenous perspective, Australia’s history is one of invasion, war, displacement and social destruction.

Content is available under the

Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike License.

Privacy Policy | Authors