Removing children from Indigenous communities has been a feature of Australian history since the early colonial period.

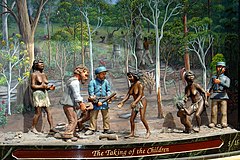

A portrayal entitled The Taking of the Children on the 1999 Great Australian Clock, Queen Victoria Building, Sydney, by artist Chris Cook.

Children began to be removed from Indigenous communities during the earliest days of non-Indigenous settlement in Australia. Children removed from their families were said to have been ‘rescued’ from their culture, as this extract from the first Sydney newspaper, the Sydney Gazette, explained in relation to one of the first children taken, the young boy known as James Bath. Young James, it said, was:

| “

|

rescued from barbarism by the events of his parents’ death, both being shot while they were engaged in plundering and laying waste the then infant settlement of Toongabbie. When the pillagers were driven off the infant was found, and compassionately adopted as a foundling by George Bath, a prisoner (Sydney Gazette, 2 December 1804).

|

”

|

Children were useful to non-Indigenous colonists in a number of ways. Some colonists wanted to see whether Indigenous people could be ‘civilised’ and in the process the gained children who also worked for them as domestic servants. Explorers valued the knowledge of country that even very small Indigenous children possessed (Reynolds, 1990, p. 165).

Over time these practices of removal came to be implemented more formally in government policy. As we learnt in last week’s study, in the late 19th century Social Darwinism and thinking about ‘race’ in biological terms came to dominate non-Indigenous thinking about Indigenous people. Those people who were of ‘mixed-race’ were then the subject of particular concern by non-Indigenous people and were seen to have both potential and to be a cause of danger:

| “

|

While the mixing of supposedly distant races was widely believed to produce inferior offspring, the infusion of ‘British blood’ was also believed to produce children who were superior to their Aboriginal ancestors. At the same time adults of mixed descent were associated with disharmony, danger and immorality, and were considered to be in need of strict controls (Haebich & Delroy, 1999, p. 18).

|

”

|

Under Protection Acts in various colonies and later Australian states, Protectors were given powers to remove children from their families (among the many powers they held over Aboriginal people’s lives). After Federation (when the colonies joined together to form the new Australian nation), the states retained control over Aboriginal affairs. This meant each state had different laws and policies. However, in the 1930s, the idea of ‘absorption’ became central to actions of Protectors to remove children in many states. Queensland was a notable exception. J. W. Bleakley, Chief Protector and Director of Native Affairs from 1913 to 1942, exercised a major influence over Queensland policy and the practices of officials as well practices on the missions. He believed firmly in the segregation of Indigenous people from non-Indigenous people:

| “

|

It is only by complete separation of the two races that we can save him (‘the Aborigine’) from hopeless contamination and eventual extinction, as well as safeguard the purity of our own blood (Chief Protector Report 1919, cited in Bringing them Home)

|

”

|

At this time ‘eugenics’, the (pseudo) science of racial improvement through good human ‘breeding’, usually focused on race, was popular around the world. A. O. Neville, was a strong advocate of these racial approaches: “[h]e claimed the ‘natural outcome’ was for the ‘blacks to go white’ through progressive intermarriage”. Under Neville’s influence the Western Australian government included “eugenic measures to ‘breed out the colour’ in the 1936 Native Administration Act” (Haebich & Delroy, 1999, p. 39. See also McGregor, 2002). These focussed on controls over who Aboriginal people could marry, as well as the removal of ‘half-caste’ children.

Aboriginal boys and men in front of a bush shelter, Groote Eylandt, c. 1933

Neville’s influence can be seen in practices in many other states, particularly the Northern Territory and NSW, with children with light skin being removed from their families and communities. In his home state of Western Australia one institution where children were taken, known as ‘Sister Kate’s’, was officially called the ‘Quarter Caste Children’s Home’ reflecting its racial purpose. Children who were described as ‘nearly white’ were taken to this home (cited in Haebich & Delroy, 1999, p.40). Children were allowed little contact with the outside world until they were sent to work in non-Indigenous homes, and, because they were not defined as being Indigenous, were forbidden contact with their families and communities because those people contact was not allowed with Aboriginal people who came under the 1936 Act (Haebich & Delroy, 1999).

In 1937 the first Conference of Commonwealth and State authorities on ‘Aboriginal Welfare’ was held in Canberra. Although the States had previously been influenced by each others’ practices, and Chief Protectors sometimes consulted with each other, this was the first time that Aboriginal affairs had been discussed at the national level. Despite some objections from Bleakley, the conference was heavily influenced by A. O. Neville, and passed a general agreement that ‘the destiny of the natives of aboriginal origin, but not of the full blood, lies in their ultimate absorption by the people of the Commonwealth, and it therefore recommends that all efforts be directed to that end’ (Commonwealth of Australia, 1937, p. 21).

You can read the full transcript of the proceedings of this Conference.

After WWII, ideas about biological absorption were discredited. Social and economic assimilation became the dominant official policy. However, removal of Aboriginal children on supposedly ‘welfare’ grounds remained common practice.

The Bringing them Home report is a very large document however it is a very important one in Australia’s Indigenous history. The Inquiry and this publication brought to light the removal of Indigenous children over generations and commented specifically on what this did to Indigenous people, social structures and families. Below are links to the National Overview section of the report, and links to two of the individual testimonies included in the report.

Commonwealth of Australia. (1997). Bringing them Home: Report of the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from their Families. Online. Part 2: Tracing the History. Chapter 2: National Overview.

Individual stories:

Peggy:

John:

PLUS read at least ONE of the following:

Robinson, S. (2003). ‘We do not want one who is too old’: Aboriginal child domestic servants in late 19th and early 20th century Queensland. In Aboriginal History. Vol 27. Pp. 162-182. Online:

OR

Wilson, C (2014). Did legalized slavery exist in Australia. Radio National. Online:

Ellinghaus, K. (2003). Absorbing the Aboriginal problem: controlling interracial marriage in the late 19th and early 20th century. In Aboriginal History. Vol 27. Online. Accessed 24/07/2015.

OR

Rolls, M. (2005). The changing politics of miscegenation. In Aboriginal History. Vol 29. Online. Accessed 29/7/15.

The Bringing them Home report found that the removal policies were an act of genocide as defined by the United Nations. This finding has been the subject of intense debate (Ellinghaus, 2009).

Key Ideas

Removing children from Indigenous communities has been a feature of Australian history since the early colonial period.

Children began to be removed from Indigenous communities during the earliest days of non-Indigenous settlement in Australia. Children removed from their families were said to have been ‘rescued’ from their culture, as this extract from the first Sydney newspaper, the Sydney Gazette, explained in relation to one of the first children taken, the young boy known as James Bath. Young James, it said, was:

Children were useful to non-Indigenous colonists in a number of ways. Some colonists wanted to see whether Indigenous people could be ‘civilised’ and in the process the gained children who also worked for them as domestic servants. Explorers valued the knowledge of country that even very small Indigenous children possessed (Reynolds, 1990, p. 165).

Over time these practices of removal came to be implemented more formally in government policy. As we learnt in last week’s study, in the late 19th century Social Darwinism and thinking about ‘race’ in biological terms came to dominate non-Indigenous thinking about Indigenous people. Those people who were of ‘mixed-race’ were then the subject of particular concern by non-Indigenous people and were seen to have both potential and to be a cause of danger:

Under Protection Acts in various colonies and later Australian states, Protectors were given powers to remove children from their families (among the many powers they held over Aboriginal people’s lives). After Federation (when the colonies joined together to form the new Australian nation), the states retained control over Aboriginal affairs. This meant each state had different laws and policies. However, in the 1930s, the idea of ‘absorption’ became central to actions of Protectors to remove children in many states. Queensland was a notable exception. J. W. Bleakley, Chief Protector and Director of Native Affairs from 1913 to 1942, exercised a major influence over Queensland policy and the practices of officials as well practices on the missions. He believed firmly in the segregation of Indigenous people from non-Indigenous people:

At this time ‘eugenics’, the (pseudo) science of racial improvement through good human ‘breeding’, usually focused on race, was popular around the world. A. O. Neville, was a strong advocate of these racial approaches: “[h]e claimed the ‘natural outcome’ was for the ‘blacks to go white’ through progressive intermarriage”. Under Neville’s influence the Western Australian government included “eugenic measures to ‘breed out the colour’ in the 1936 Native Administration Act” (Haebich & Delroy, 1999, p. 39. See also McGregor, 2002). These focussed on controls over who Aboriginal people could marry, as well as the removal of ‘half-caste’ children.

Neville’s influence can be seen in practices in many other states, particularly the Northern Territory and NSW, with children with light skin being removed from their families and communities. In his home state of Western Australia one institution where children were taken, known as ‘Sister Kate’s’, was officially called the ‘Quarter Caste Children’s Home’ reflecting its racial purpose. Children who were described as ‘nearly white’ were taken to this home (cited in Haebich & Delroy, 1999, p.40). Children were allowed little contact with the outside world until they were sent to work in non-Indigenous homes, and, because they were not defined as being Indigenous, were forbidden contact with their families and communities because those people contact was not allowed with Aboriginal people who came under the 1936 Act (Haebich & Delroy, 1999).

In 1937 the first Conference of Commonwealth and State authorities on ‘Aboriginal Welfare’ was held in Canberra. Although the States had previously been influenced by each others’ practices, and Chief Protectors sometimes consulted with each other, this was the first time that Aboriginal affairs had been discussed at the national level. Despite some objections from Bleakley, the conference was heavily influenced by A. O. Neville, and passed a general agreement that ‘the destiny of the natives of aboriginal origin, but not of the full blood, lies in their ultimate absorption by the people of the Commonwealth, and it therefore recommends that all efforts be directed to that end’ (Commonwealth of Australia, 1937, p. 21).

You can read the full transcript of the proceedings of this Conference.

After WWII, ideas about biological absorption were discredited. Social and economic assimilation became the dominant official policy. However, removal of Aboriginal children on supposedly ‘welfare’ grounds remained common practice.

Required Reading

The Bringing them Home report is a very large document however it is a very important one in Australia’s Indigenous history. The Inquiry and this publication brought to light the removal of Indigenous children over generations and commented specifically on what this did to Indigenous people, social structures and families. Below are links to the National Overview section of the report, and links to two of the individual testimonies included in the report.

Commonwealth of Australia. (1997). Bringing them Home: Report of the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from their Families. Online. Part 2: Tracing the History. Chapter 2: National Overview.

Individual stories:

Peggy:

John:

PLUS read at least ONE of the following:

Robinson, S. (2003). ‘We do not want one who is too old’: Aboriginal child domestic servants in late 19th and early 20th century Queensland. In Aboriginal History. Vol 27. Pp. 162-182. Online:

OR

Wilson, C (2014). Did legalized slavery exist in Australia. Radio National. Online:

Ellinghaus, K. (2003). Absorbing the Aboriginal problem: controlling interracial marriage in the late 19th and early 20th century. In Aboriginal History. Vol 27. Online. Accessed 24/07/2015.

OR

Rolls, M. (2005). The changing politics of miscegenation. In Aboriginal History. Vol 29. Online. Accessed 29/7/15.

The Bringing them Home report found that the removal policies were an act of genocide as defined by the United Nations. This finding has been the subject of intense debate (Ellinghaus, 2009).

Content is available under the

Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike License.

Privacy Policy | Authors