The term ‘Stolen Generations’ is commonly used to define the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who were forcibly removed from their families and kinship networks as children as a result of past government policies and missionary practice.

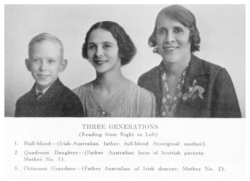

Figure 1: In his 1947 book about Australian race relations, A. O. Neville provided visual support for his biological absorptionist theories. From Neville, Australia’s Coloured Minority, facing p. 72.

This topic deals with some particularly tragic, traumatic and difficult to confront histories. As indicated in last week’s reading, from at least the early twentieth century so-called ‘half-caste’ Aboriginal children were routinely removed from their families. In the earlier phases of this policy, they were sent to missions or government institutions that usually trained the girls for domestic service and boys for low status labouring jobs (Walden, 1995). Many were assigned to work for very low wages and often they never saw even this money – the Aborigines Protection Boards kept the money in ‘trust’. Within other missions, children were divided from their families and placed in separate dormitories. Later, some children were sent to be raised in white foster families.

Early child removals were often informal. Later, the Aborigines Protection Acts and various other pieces of legislation provided the legal framework for these practices. The explicit aim of removal was to “to control the reproduction of Indigenous people with a view to ‘merging’ or ‘absorbing’ them into the non-Indigenous population” (Commonwealth of Australia, 1997, p.25 of PDF file). It was envisaged that ‘half-caste’ Aboriginal women would marry white men. The ‘Aboriginal problem’, as it was termed at the time, would thus be ‘bred out’ of existence. Aboriginal people would become white (McGregor, 2002).

One of the key architects of the policy of ‘biological absorption’ was A. O. Neville, the Chief Protector of Aborigines in Western Australia from 1915 to 1940. This is how Neville depicted his policy:

‘Biological absorption’ was the extreme end of the spectrum of policies of assimilation.

Bringing them Home, the Report of the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from their Families, tabled in 1997, brought widespread attention to the harm that was caused by these removal policies. The Inquiry had been conducted over two years, and had taken evidence orally or in writing from 535 Indigenous people throughout Australia concerning their experiences of the removal policies. Witnesses shared highly personal experiences and the Inquiry’s report contains hundreds of extracts from their testimony.

The Bringing them Home Report outlined the extent of child removal as follows:

| “

|

Nationally we can conclude with confidence that between one in three and one in ten Indigenous children were forcibly removed from their families and communities in the period from approximately 1910 until 1970. In certain regions and in certain periods the figure was undoubtedly much greater than one in ten. In that time not one Indigenous family has escaped the effects of forcible removal (confirmed by representatives of the Queensland and WA Governments in evidence to the Inquiry). Most families have been affected, in one or more generations, by the forcible removal of one or more children (HREOC, 1997, Chapter 2).

|

”

|

Key Ideas

The term ‘Stolen Generations’ is commonly used to define the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who were forcibly removed from their families and kinship networks as children as a result of past government policies and missionary practice.

This topic deals with some particularly tragic, traumatic and difficult to confront histories. As indicated in last week’s reading, from at least the early twentieth century so-called ‘half-caste’ Aboriginal children were routinely removed from their families. In the earlier phases of this policy, they were sent to missions or government institutions that usually trained the girls for domestic service and boys for low status labouring jobs (Walden, 1995). Many were assigned to work for very low wages and often they never saw even this money – the Aborigines Protection Boards kept the money in ‘trust’. Within other missions, children were divided from their families and placed in separate dormitories. Later, some children were sent to be raised in white foster families.

Early child removals were often informal. Later, the Aborigines Protection Acts and various other pieces of legislation provided the legal framework for these practices. The explicit aim of removal was to “to control the reproduction of Indigenous people with a view to ‘merging’ or ‘absorbing’ them into the non-Indigenous population” (Commonwealth of Australia, 1997, p.25 of PDF file). It was envisaged that ‘half-caste’ Aboriginal women would marry white men. The ‘Aboriginal problem’, as it was termed at the time, would thus be ‘bred out’ of existence. Aboriginal people would become white (McGregor, 2002).

One of the key architects of the policy of ‘biological absorption’ was A. O. Neville, the Chief Protector of Aborigines in Western Australia from 1915 to 1940. This is how Neville depicted his policy:

‘Biological absorption’ was the extreme end of the spectrum of policies of assimilation.

Bringing them Home, the Report of the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from their Families, tabled in 1997, brought widespread attention to the harm that was caused by these removal policies. The Inquiry had been conducted over two years, and had taken evidence orally or in writing from 535 Indigenous people throughout Australia concerning their experiences of the removal policies. Witnesses shared highly personal experiences and the Inquiry’s report contains hundreds of extracts from their testimony.

The Bringing them Home Report outlined the extent of child removal as follows:

Content is available under the

Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike License.

Privacy Policy | Authors